The Elixir Telescope

Part 3 : Raytracing a parabolic mirror from scratch

Entries up to this point :

In the last entry of this series, we learned that while an ellipsoidal mirror would be ideal for imaging a subject at a known distance, I’d fall back to a regular parabolic mirror for its versatility. But a few questions are still up.

- What would be the image formation distance for an object not located at infinity ?

- What would be the resultant spherical aberration for an object not located at infinity ?

To answer those two questions, I first made a prototype with a visualizer in Vue + canvas, and will then port it to Elixir (and Elixir + Rust through rustler) for the next post, because I’ll soon need to use those simulations server-side.

Raytracing a parabolic mirror

The equation of a parabola, symmetric on the Y axis, can be defined as y^2 = 4ax, where a is the focal point (so, the paraxial focal length) of the parabola.

We’ll work with our parabola symmetric to the X axis, so we’ll go from Y values to X values, to simulate rays hitting the parabola at height y.

/*

y*y = 4fx

y*y/4/f = x

*/

const x_coord_on_parabola = (focal_length: number, y: number) => {

return y * y / 4 / focal_length;

};

With that, we can draw a parabolic mirror slice of radius r, by getting x coordinates every mm for y values -r to r. I define a few types beforehand.

export type Point = {

x: number,

y: number

};

export type Segment = {a: Point, b: Point};

export const parabola_coords = (radius: number, focal_length: number): Point[] => {

const out = [];

for (let y = -1 * radius; y < radius; y += 1) {

const x = x_coord_on_parabola(focal_length, y);

out.push({ x, y });

}

return out;

};

That’s enough to draw the parabolic shape ! I’ll define a few canvas helpers to handle offset from the top left corner, antialiasing, and zoom :

const to_x = (n: number) => zoom.value * (n + x_off) + 0.5;

const to_y = (n: number) => zoom.value * (n + y_off) + 0.5;

const lineTo = (x: number, y: number) => ctx.lineTo(to_x(x), to_y(y));

const moveTo = (x: number, y: number) => ctx.moveTo(to_x(x), to_y(y));

const arc = (x: number, y: number, r: number, a: number) => ctx.arc(to_x(x), to_y(y), r, 0, a);

const draw_segment = (s: Segment) => {

ctx.beginPath();

moveTo(s.a.x, s.a.y);

lineTo(s.b.x, s.b.y);

ctx.stroke();

};

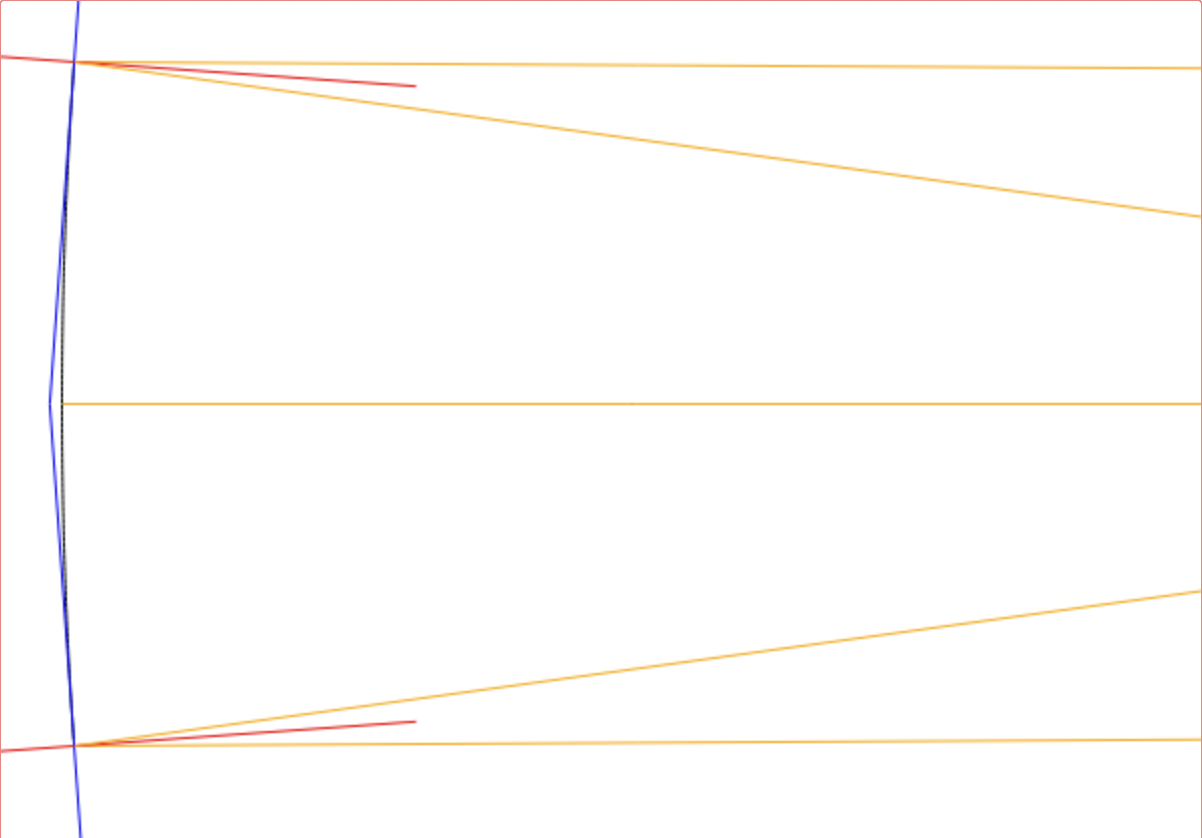

And voilà, here’s a parabolic surface (and its axis).

const parabola = () => {

ctx.beginPath();

parabola_coords(radius, focal_length).forEach(p => {

lineTo(p.x, p.y);

});

ctx.stroke();

};

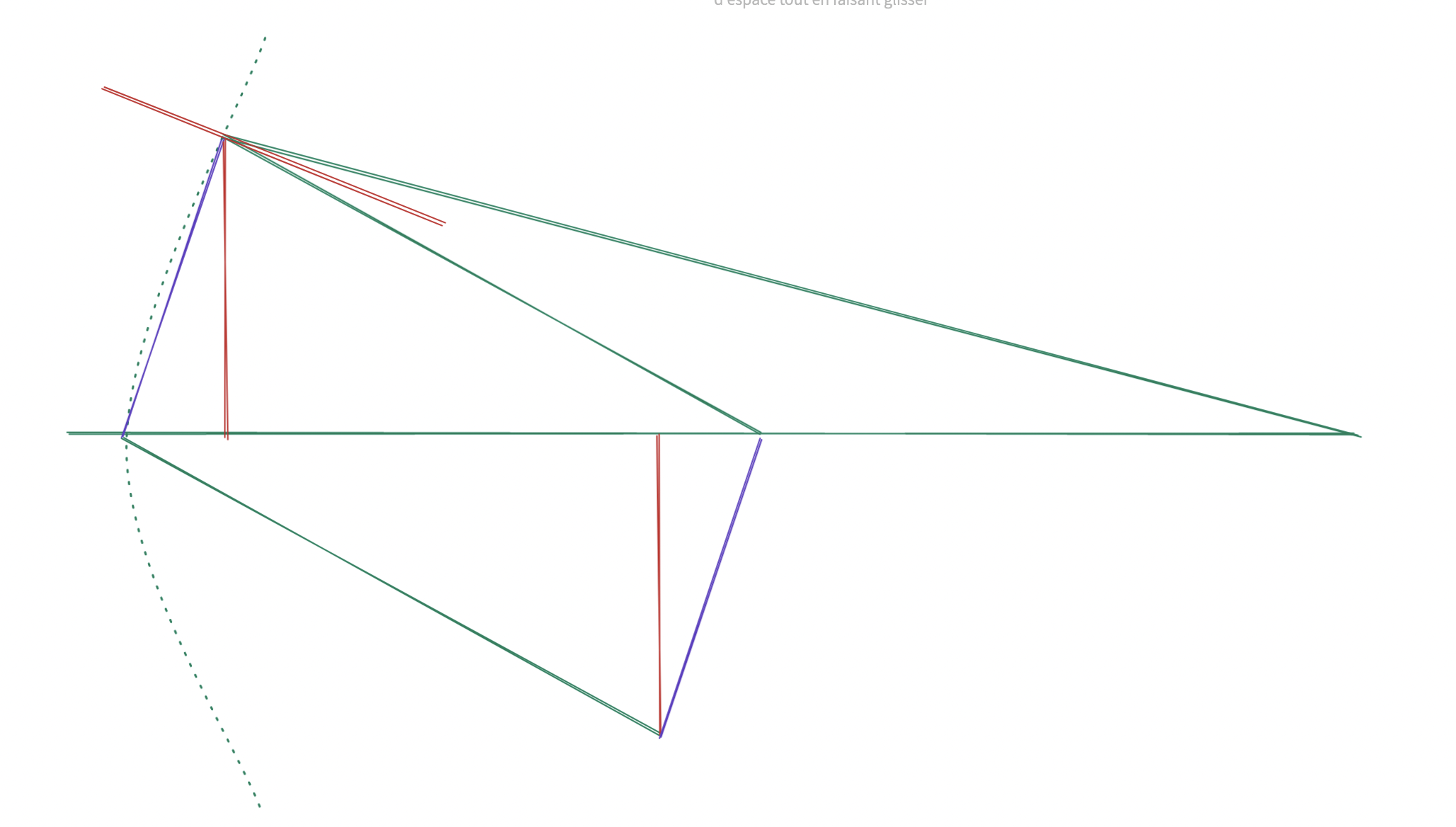

I then have drawn the beam of rays coming from infinity, hitting the parabola, and reflecting back to (focal_length, 0).

The next step is to be able to actually trace rays coming from a non-infinity distance, and bouncing on the parabolic surface. For that, you just need to remember that a ray reflects on the other side of the normal to a curve, with the same angle to this normal.

We first need to get tangents to points on the parabola, then, from there, normals to points on the parabola. The tangent to a point on a curve can be seen as the derivative of the curve at this point, and the normal can be seen as the tangent rotated 90°.

export const tangent_coords = (focal_length: number, y: number): Segment => {

const x = x_coord_on_parabola(focal_length, y);

const dx = -2 * x;

const dy = -y;

return {

a: {

x: -x,

y: 0,

},

b: {

x: x - dx,

y: y - dy,

}

};

};

export const normal_coords = (focal_length: number, y: number): Segment => {

const x = x_coord_on_parabola(focal_length, y);

const dx = -2 * x;

const dy = -y;

return {

a: {

x: -dy + x,

y: dx + y,

},

b: {

x: dy + x,

y: -dx + y,

}

};

};

Drawing that, we get tangents in blue and normals in red :

We can see that the normal to a point hit on the parabola bisects the angle between the original ray and the reflected ray. But that’s just the law of reflection.

So, we first need to get rays from a non-infinity distance.

export const non_parallel_rayfan_coords = (focal_length: number, radius: number, source_distance: number, rays: number): Segment[] => {

const out: Segment[] = [];

const base_y = -radius;

const base_x = source_distance;

const step = Math.abs(radius) / rays * 2;

for (let i = 0; i <= rays; i++) {

const y = base_y + i * step;

const x = x_coord_on_parabola(focal_length, y);

out.push({

a: {

x,

y,

},

b: {

x: base_x,

y: 0,

}

});

}

return out;

};

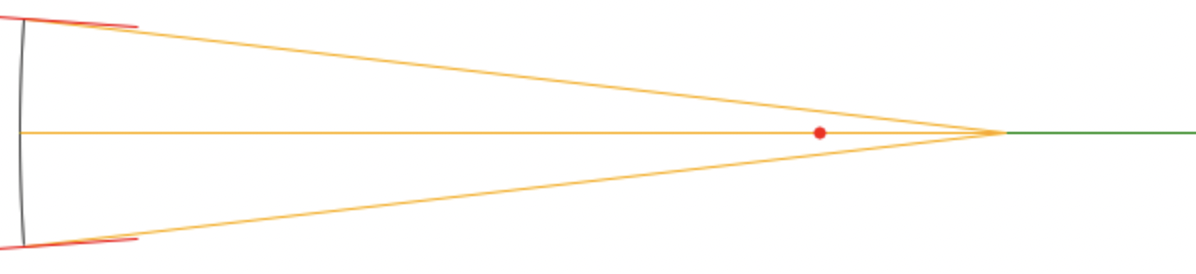

We draw them :

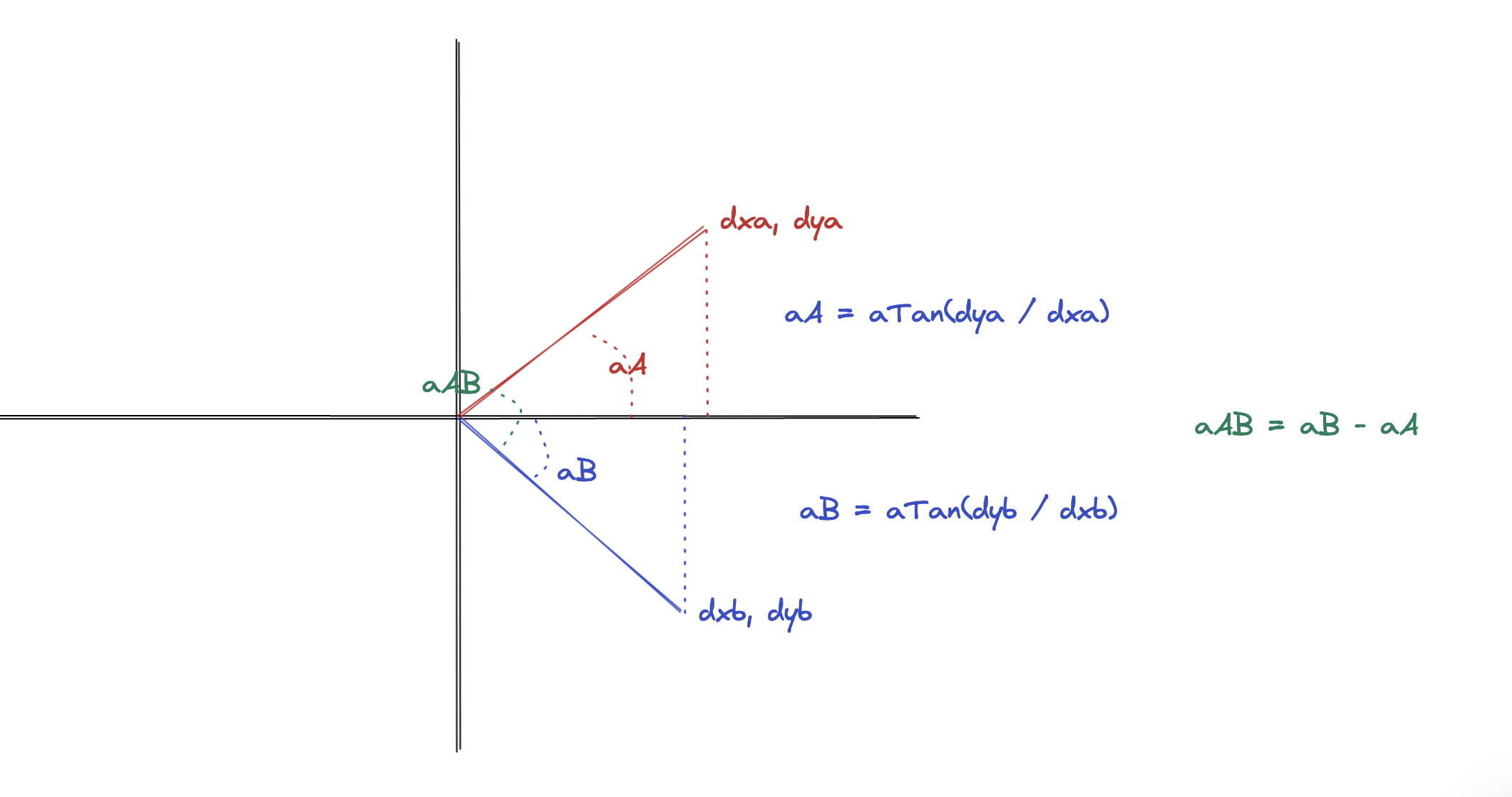

And we’ll compute their reflections, that is, the ray going from the (x, y) point on the parabola, to an (x1, 0) point on the X axis. For that, I need to know the angle between the incoming ray and the normal. I’ve been able to transform the problem to something else. I know how to get angles in a right-angled triangle. So I can just “translate” my segments to have their first point at the (0, 0) coordinate, and see the X axis as a side of the triangle.

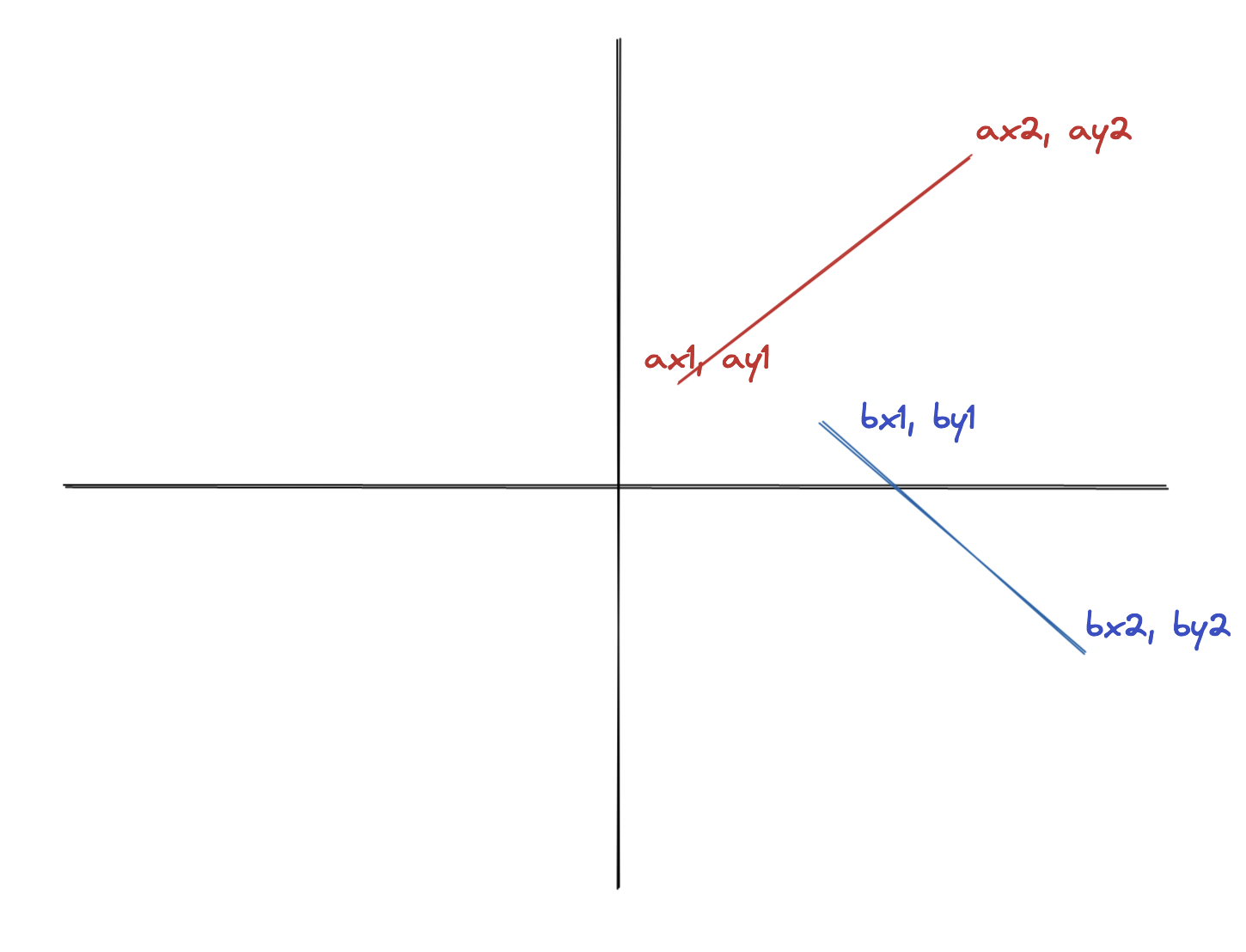

Two segments :

Two segments moved back to origin simplify the problem :

Translated into code :

const angle_between_segments = (a: Segment, b: Segment) : number => {

return angle_with_x_axis(b) - angle_with_x_axis(a);

};

const angle_with_x_axis = (s: Segment) : number => {

const derived = segment_delta(s);

return Math.atan2(derived.b.y, derived.b.x);

};

const segment_delta = (s: Segment) : Segment => {

return {

a: {

x: 0,

y: 0,

},

b: {

x: s.b.x - s.a.x,

y: s.b.y - s.a.y

},

};

};

We can now get the angle between a ray and the normal :

const normal = normal_coords(focal_length, y);

const angle = angle_between_segments(ray, normal);

const output_angle = angle_with_x_axis(ray) + (2 * angle);

Then, as we have an origin point (x, y) on the parabola, and an angle from that point, we can just project it to get the X coordinate where Y = 0. It took me a fair bit of imaginary triangles to figure it out :

But it finally clicked :

export const point_and_angle_to_x_coord = (p: Point, angle: number) => {

let slope = Math.tan(angle);

let x = ((slope * p.x) - p.y) / slope;

return x;

};

We can now assemble all of that to get our reflected ray :

export const reflection_coords = (focal_length: number, y: number, source_distance: number) : Segment => {

const x = x_coord_on_parabola(focal_length, y);

const v1 : Segment = {

b: {

x,

y,

},

a: {

x: source_distance,

y: 0,

},

};

const normal = normal_coords(focal_length, y);

const angle = angle_between_segments(v1, normal);

const output_angle = angle_with_x_axis(v1) + (2 * angle);

const x_coord = point_and_angle_to_x_coord({x, y}, output_angle);

return {

a: {

x,

y,

},

b: {

x: x_coord,

y: 0

}

};

};

Here is the resulting interactive widget (mobile users, you can scroll the graph to the right):

Answering the initial questions

-

Q : What would be the image formation distance for an object not located at infinity ?

-

A : With our 57mm radius / 400mm f.l. parabolic mirror, an object located at 10 meters images at 416.67mm from the vertex of the mirror.

-

Q : What would be the resultant spherical aberration for an object not located at infinity ?

-

A : With our 57mm radius / 400mm f.l. parabolic mirror, an object located at 10 meters has 0.17mm of longitudinal aberration due to residual spherical aberration.

Why did I need this information ?

Remember that my goal is to simulate the telescope in software before plugging the physical telescope to the same software. I want to simulate depth of field on an image. For that, I need to know where an object at a known distance images from the mirror. Yes, I could have used OSLO Edu or any raytracing program for that. But that’s no fun !

Benchmarking

Here are benchmark results for Elixir or Elixir + Rustler implementations. I used a high number of rays to lessen the cost of calling the FFI.

Here is the commit with the rust implementation. It is very close to the Typescript one and could probably be optimized a lot. Still, there’s a 2x improvement from the elixir implementation. A 2x reduction in compute, for free, is always a good thing.

for n <- [1001, 10001, 100001] do

Benchee.run(

%{

"Elixir, #{n} rays" => fn -> Optics.Parabola.non_parallel_rayfan_coords(400.0, 57.0, 10000.0, n) end,

"Rust , #{n} rays" => fn -> Optics.Parabola.non_parallel_rayfan_coords_rs(400.0, 57.0, 10000.0, n) end

})

end

$ MIX_ENV=prod mix run bench/rays.exs

Operating System: macOS

CPU Information: Apple M1

Number of Available Cores: 8

Available memory: 16 GB

Elixir 1.14.0

Erlang 25.0

Benchmark suite executing with the following configuration:

warmup: 2 s

time: 5 s

memory time: 0 ns

reduction time: 0 ns

parallel: 1

inputs: none specified

Estimated total run time: 14 s

Benchmarking Elixir, 10001 rays ...

Benchmarking Rust , 10001 rays ...

Name ips average deviation median 99th %

Rust , 10001 rays 177.48 5.63 ms ±35.69% 5.66 ms 8.39 ms

Elixir, 10001 rays 111.83 8.94 ms ±9.72% 8.58 ms 11.39 ms

Comparison:

Rust , 10001 rays 177.48

Elixir, 10001 rays 111.83 - 1.59x slower +3.31 ms

Operating System: macOS

CPU Information: Apple M1

Number of Available Cores: 8

Available memory: 16 GB

Elixir 1.14.0

Erlang 25.0

Benchmark suite executing with the following configuration:

warmup: 2 s

time: 5 s

memory time: 0 ns

reduction time: 0 ns

parallel: 1

inputs: none specified

Estimated total run time: 14 s

Benchmarking Elixir, 100001 rays ...

Benchmarking Rust , 100001 rays ...

Name ips average deviation median 99th %

Rust , 100001 rays 15.62 64.03 ms ±43.96% 58.55 ms 106.98 ms

Elixir, 100001 rays 8.31 120.40 ms ±15.90% 117.09 ms 159.32 ms

Comparison:

Rust , 100001 rays 15.62

Elixir, 100001 rays 8.31 - 1.88x slower +56.38 ms