Distributed transcription with Whisper and Elixir

After a first post about Bumblebee and Whisper, I’ve had the pleasure of working more with whisper in the context of Audioskop. Audioskop will have to transcribe quite a lot of audio, and we prefer to do that locally while the project is being developed.

Note : Audioskop will be fully open-sourced when the website publicly opens and replaces the current landing page :^). It is developed as a Phoenix + Liveview app.

I had to implement a few things beyond my simple first encounter with Whisper in november.

Choosing a model

The module that actually runs transcriptions is still a simple GenServer, loading the model chosen by the instance manager.

model = Options.get_whisper_model().value

{:ok, whisper} = Bumblebee.load_model({:hf, model})

{:ok, featurizer} = Bumblebee.load_featurizer({:hf, model})

{:ok, tokenizer} = Bumblebee.load_tokenizer({:hf, model})

{:ok, generation_config} = Bumblebee.load_generation_config({:hf, model})

The Options helper is a convenience module that generates getter/setter functions from a list of tuples in a module attribute. That’s quite handy to get auto-completion on available options.

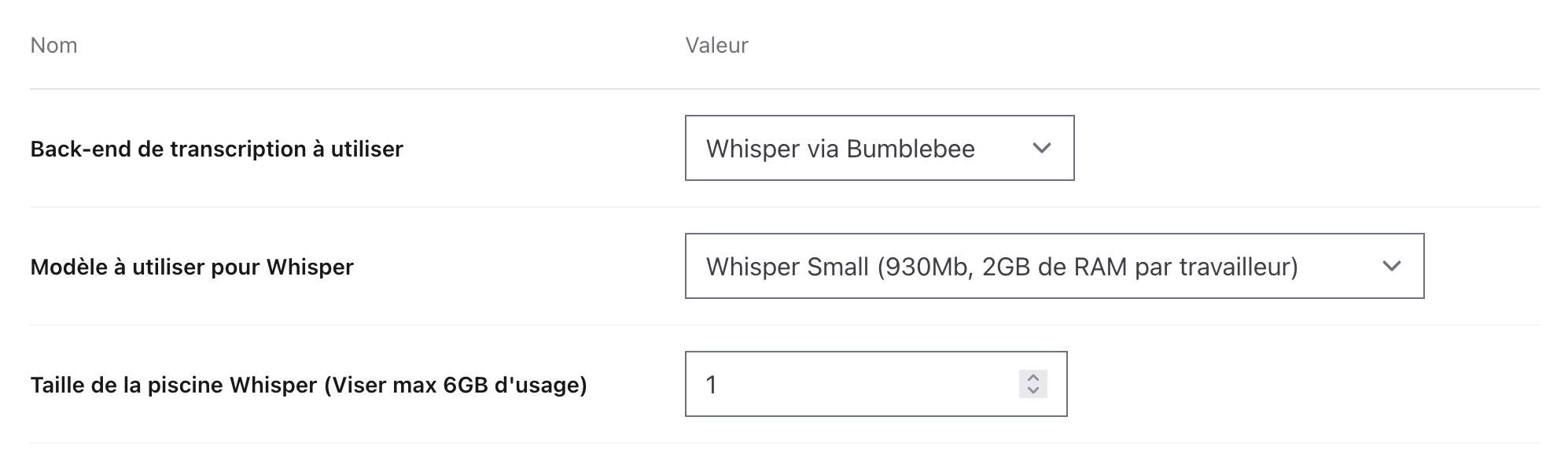

{:transcription_backend, "Back-end de transcription à utiliser", :select, :none,

[

{:whisper, "Whisper via Bumblebee"},

{:google, "Google Speech to Text API"},

{:none, "Aucun"}

]

},

{:whisper_model, "Modèle à utiliser pour Whisper", :select, "openai/whisper-small",

[

{"openai/whisper-small", "Whisper Small (930Mb, 2GB de RAM par travailleur)"},

{"openai/whisper-medium", "Whisper Medium (3060Mb, ~6GB de RAM par travailleur)"}

]},

{:whisper_workers, "Taille de la piscine Whisper (Viser max 6GB d'usage)", :number, 3},

An associated LiveView conveniently renders all of those options to the instance super-admin, handling casts from and to select fields, dates, numbers, and text. We can see that I also define a number of workers. I’ve yet to run extensive benchmarks (which are quite expensive to run since I transcribe 30 minutes tracks), but I’ve felt that 2 concurrent transcriptions on my MacBook seem to complete faster than sequentially.

Running a transcription

My user-land code was roughly this :

Audioskop.Tracks.transcribe_track(track)

which hid the call to the transcription server.

Handling failures

My first improvement was to wrap the actual transcription in an Oban Job. As a transcription can take a bit of time, it allows us to not lose work in case the server goes down. As we are locally using the app right now until most of the tracks have been transcribed, “server goes down” can mean shutting down a laptop before a transcription ended..

Audioskop.Jobs.TranscribeTrack.register(track)

The job has a few things going on, but these steps are the most relevant, where run/1 is called by Oban.Worker’s perform/1 callback with the track fetched from the DB:

def run(%Track{} = track) do

Track.change_status(track, :transcription_started)

path = Track.absolute_location(track.storage_path)

%{chunks: c} = Transcriber.transcribe(path)

Track.change_status(track, :transcription_ended)

Audioskop.Topics.publish(:transcription_ended, track)

c

end

Splitting the work in 30 seconds units

Before being able to run transcriptions of long tracks, I’ve found myself needing to split the tracks into 30 seconds chunks, otherwise my computer started to become a valid living room heating applicance, and never really completed the task. I thought by reading Bumblebee material that this was done by the library internally, but must have been mistaken as I did not find this affirmation anywhere again.

%{chunks: c} = SplittingTranscriber.transcribe(path)

The job was updated to give a call to a SplittingTranscriber module. I chose this strategy to avoid stuffing the Transcriber GenServer with other tasks than getting a file path to pass to the Nx serving.

The SplittingTranscriber module first splits the file with ffmpeg.

Note that the SplittingTranscriber is not a GenServer, just a plain module to organize code.

def transcribe(file) do

path = get_random_dir()

System.cmd("ffmpeg", [

"-i",

file,

"-f",

"segment",

"-segment_time",

"30",

"-c",

"copy",

"#{path}/out_%03d.mp3"

])

File names are then sorted in order, and a bunch of Tasks is awaited on to get the results.

output = files

|> Enum.map(fn f ->

Task.async(fn ->

Audioskop.Whisper.Transcriber.transcribe(f)

end)

end)

|> Task.await_many(:infinity)

I then simply re-assembled the chunks in a single list, while re-mapping their timecodes. Here, we get a lot of convenience out of Task.await_many, that guarantees the output will be in-order.

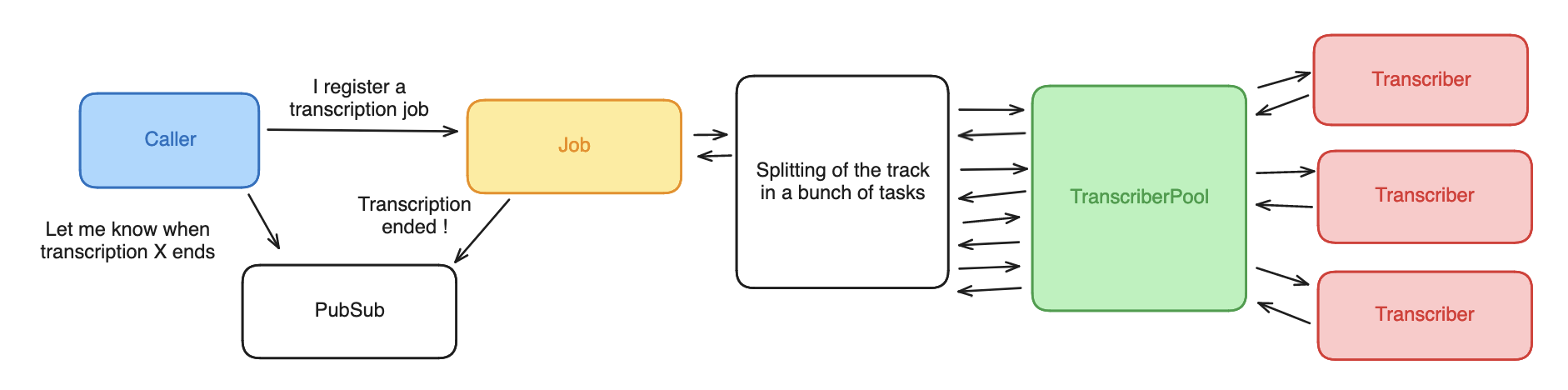

Splitting the work between a few workers

I then moved to run more than one concurrent transcription. Again, I did not want to inflate my Transcriber server code.

I introduced another process, TranscriberPool, that exposes a transcribe/1 function, while under the hood distributing the work between multiple workers.

def start_link(_) do

workers = get_n_workers()

log(

"Starting TranscriberPool with #{workers} workers. You can change that setting in your instance options."

)

GenServer.start_link(

__MODULE__,

%{

available_workers: start_workers(workers),

busy_workers: [],

pending_transcriptions: []

},

name: get_name()

)

end

Internally, I differentiate the situation where no workers are available from the situation where workers are available :

def handle_call({:transcribe, file}, from, %{available_workers: []} = state) do

log("No workers available, enqueuing")

{:noreply, enqueue(state, file, from)}

end

def handle_call({:transcribe, file}, from, %{available_workers: [h | t]} = state) do

log("Got request to transcribe")

{:noreply, process(state, file, from, h, t)}

end

I use the {:noreply, state} pattern to later reply with GenServer.reply when the actual transcription is done.

def process(state, file, from, selected_worker, remaining_workers) do

target = self()

Task.start(fn ->

transcription = Transcriber.transcribe(selected_worker, file)

Process.send_after(

target,

{:transcription_ended, transcription, from, selected_worker},

100

)

end)

%{

state

| available_workers: remaining_workers,

busy_workers: [selected_worker | state.busy_workers]

}

end

def handle_info({:transcription_ended, transcription, from, selected_worker}, state) do

log("Transcription done, replying")

GenServer.reply(from, transcription)

{:noreply, free_worker(state, selected_worker)}

end

The free_worker function updates the state and sends a :pickup_work message for the pool to maybe dequeue a task from the queue after a small pause.

At this point, the general process looks like this :

To this day, I still have doubts on the relevance of distributing the tasks between a few processes on a single node. I do not understand how my M1 Macbook would benefit from running two concurrent whisper instances instead of two sequential transcriptions with one instance, but it felt quicker in my experiments with longer tracks. This needs to be benchmarked, but what is interesting to me is the performance over 30 minute tracks. Maybe storing the transcription time with the tracks would be useful, allowing me to have a better idea of how this compares across hardware after a few months ?

Error unit

At this point, I was quite happy with the process, but the error handling could be discussed. The error unit is the Job, that is, if a single sub-transcription task fails, the job fails. To me, this is relevant, as a partially transcribed track does not make sense in the context of Audioskop. We could argue that this is wasted compute if a single sub-transcription fails. But maybe caching the transcription result of an audio fragment, going from audio file hash to transcript, and deleting this cache upon job completion would fill that use case without supervising the smaller work units. When the job gets scheduled again, all the sub-transcriptions that succeeded would be fetched from the cache, and only those that failed would go through the model again.

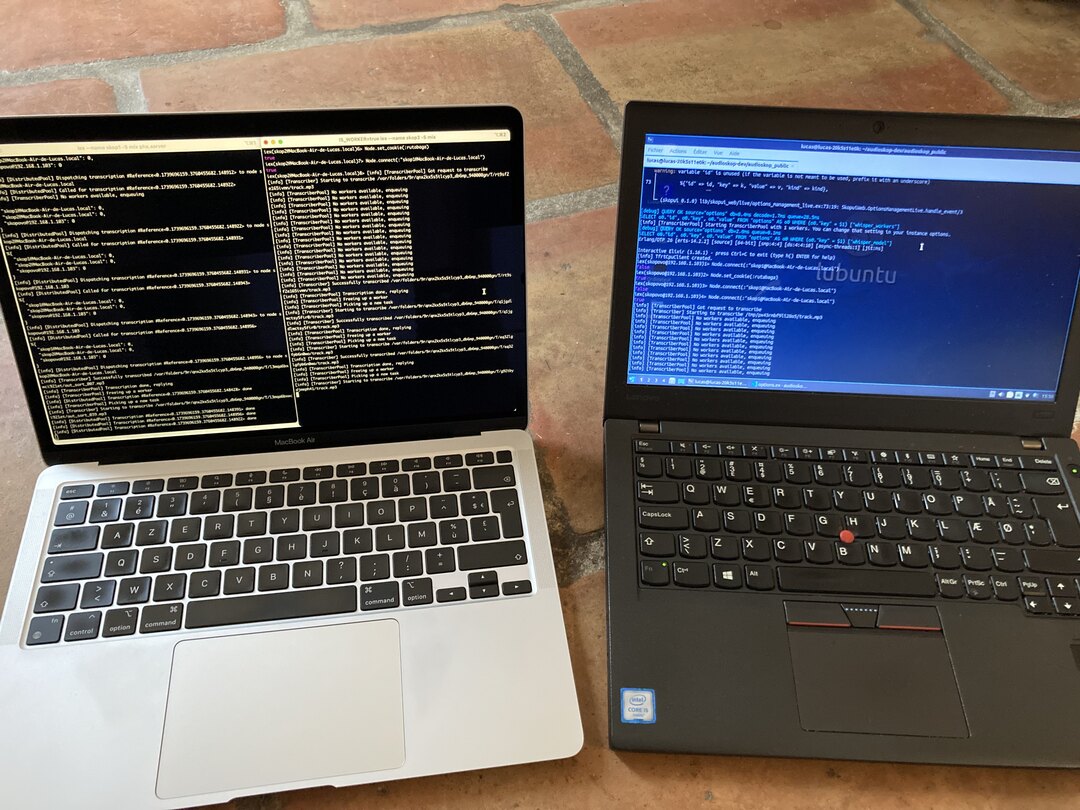

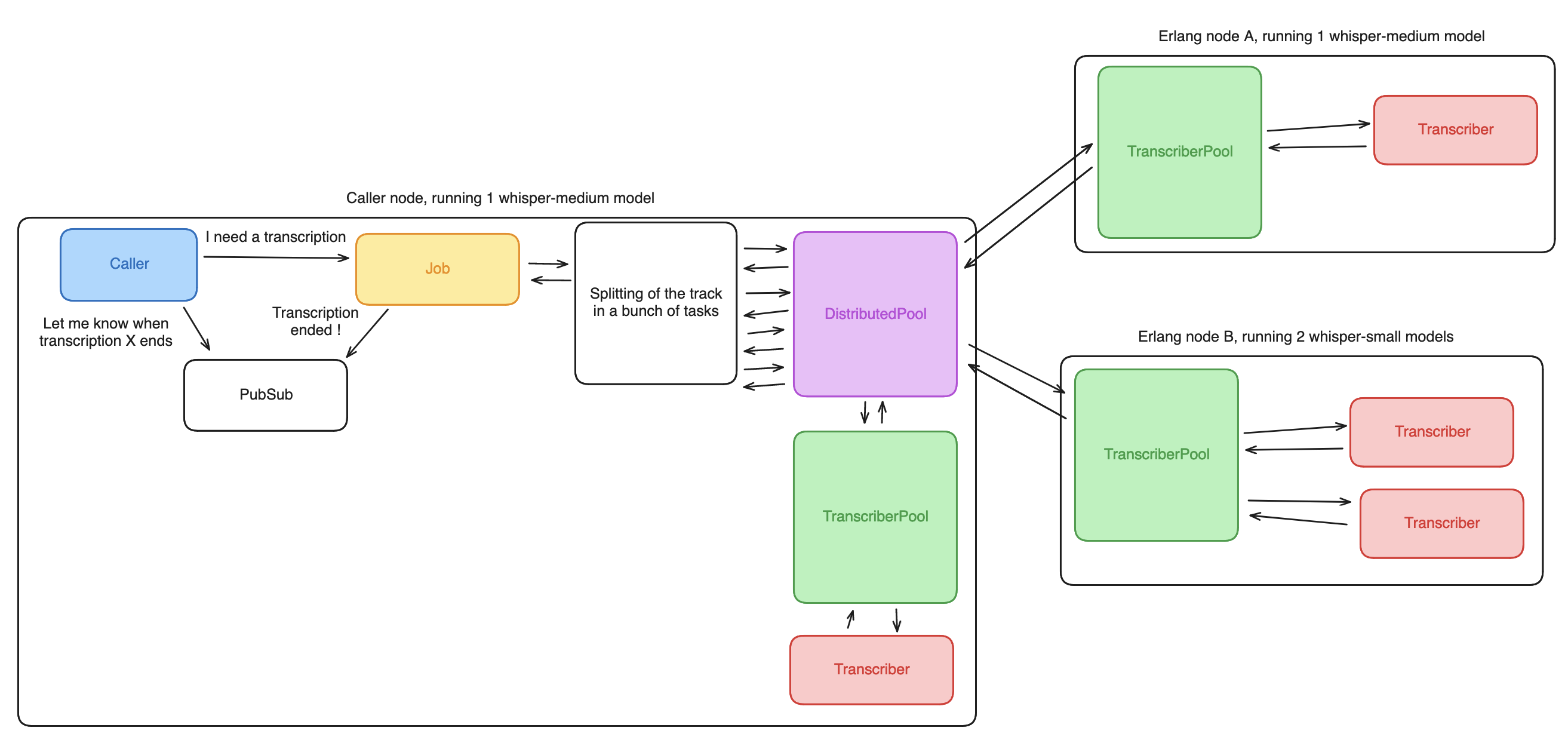

Splitting the work between a few computers

With all those changes quite easily allowed by Elixir, I started to wonder about distribution. Sometimes I develop the app on my MacBook, sometimes on a lower-powered Lenovo x270 thinkpad running Lubuntu.

This is important to me, because we want Audioskop to be able to be run by other nonprofits than ours, maybe using lower-end hardware. It’s easy to get a bit lost in developer comfort and run the largest whisper model on the beefiest Mac laptop available, but allowing the app to be used at a lower initial cost is also nice. This is why we will also support plain-text imports of transcriptions, and delegation to cloud backends (Google being quite effective and cheap at transcribing French), making Whisper an optional backend.

So, while I’m at home, why not harness that additionnal power ?

To be able to distribute the work between computers, I changed this call :

Audioskop.Whisper.Transcriber.transcribe(f)

that had already been changed to

Audioskop.Whisper.TranscriberPool.transcribe(f)

to

Audioskop.Whisper.DistributedPool.transcribe(f)

What I like is that every improvement has been a one-line change on the call sites, and transparent to the userland code after the first change that went from synchronously transcribing to using a Job.

I introduced the DistributedPool module, a GenServer that asks for connected nodes how many available workers they have in their TranscriberPool :

def available_workers() do

for n <- [node() | Node.list()] do

{n, :erpc.call(n, Audioskop.Whisper.TranscriberPool, :available_workers, [])}

end

|> Enum.into(%{})

end

def handle_call({:transcribe, file}, from, state) do

ref = make_ref()

log("Called for transcription #{inspect(ref)}")

new_state = available_workers()

{target, _} = Enum.random(new_state)

log("Dispatching transcription #{inspect(ref)} to node #{target}")

Task.start(fn ->

r =

if target == node() do

Audioskop.Whisper.TranscriberPool.transcribe(file)

else

binary = File.read!(file)

:erpc.call(

target,

Audioskop.Whisper.TranscriberPool,

:transcribe_binary,

[binary],

:infinity

)

end

log("Transcription #{inspect(ref)} done")

GenServer.reply(from, r)

end)

{:noreply, new_state}

end

We can see that I do not really use the “available workers” information yet, except as a list of online nodes. Because that does not really reflect transcription speed or power. I should find another metric to advertise to distribute the sub-tasks to the various nodes. For now, I just rely on a random distribution between connected nodes, which should be eventually fair in the amount of jobs dispatched, but definitely not in regards to processing power.

To use that distributed example, I introduced an environment variable, IS_WORKER, that when set, only starts the TranscriberPool instead of the whole application. I also do not start the Phoenix app on that node (computer).

IS_WORKER=1 iex -name skoplenovo -S mix

On the main computer, I set the number of whisper workers to 1, and started 2 nodes.

iex -name skop1 -S mix phx.server

IS_WORKER=1 iex -name skop2 -S mix

On the main node, and the two worker nodes, I set the same Erlang cookie :

Node.set_cookie(:rutabaga)

Then, on the two worker nodes, connected to the main node :

Node.connect(:"skop1@MacBook-Air-de-Lucas.local")

What’s amazing in that - and also not spectacular at all for BEAM-people - is that there’s nothing more to do. The three nodes are connected and can talk.

I then clicked on the “transcribe” button in Audioskop’s UI on my main computer, and …

Both computers happily transcribed my track :^) .

Going from the first state with a single synchronous process to this last state, where the fact that “Erlang node A” and “Erlang node B” are two physical computers and that the “Caller node” is co-located on the same host than “Erlang node A” has no incidence, took about 150 lines of library-free code - (not discounting Oban, of course, that gives a lot for free too) -, to change a synchronous process to a concurrent and distributed system. I did not have to wrestle with order-of-execution, locks, or any concurrency primitives that are a given on our platform.

Of course, if something goes wrong now, it goes distributedly wrong. I don’t think I will keep and maintain these features in the main branch. But going from zero to distributed transcription over LAN with only applicative code, no system configuration, felt really great.

Happy distributed hacking !