Playing with HTML5 Canvas from Elixir

I’m exploring little things in building a game, and stumbled on these thoughts :

- I really like the HTML5 Canvas API as I grew to be familiar with it

- I wish I could use it in a transparent way from Elixir

A quick experiment lead me to write some code to get the ball rolling. My small game is a circular PONG game. Circular PONG is great because there are all sorts of little trigonometry tricks to handle the required math in a laid-back way, which makes it a great teaching material, because we can really build a small game without thinking too much about physics and geometry.

Game state

Here’s my game state when it starts. Three players (paddles) are represented by their angular start and end positions, and a ball is represented by the (normalized) radius it sits on, and the angle (in radians) giving its direction.

%Pong2pi.Game{

difficulty: 0.3,

players: [

%Pong2pi.Player{

pos: 0.3141592653589793,

speed: 0,

tilt: 0,

start_pos: 0,

end_pos: 0.6283185307179586

},

%Pong2pi.Player{

pos: 2.408554367752175,

speed: 0,

tilt: 0,

start_pos: 2.0943951023931957,

end_pos: 2.7227136331111543

},

%Pong2pi.Player{

pos: 4.502949470145371,

speed: 0,

tilt: 0,

start_pos: 4.188790204786391,

end_pos: 4.81710873550435

}

],

ball: %Pong2pi.Ball{radius: 0, angle: 0, speed: 0}

}

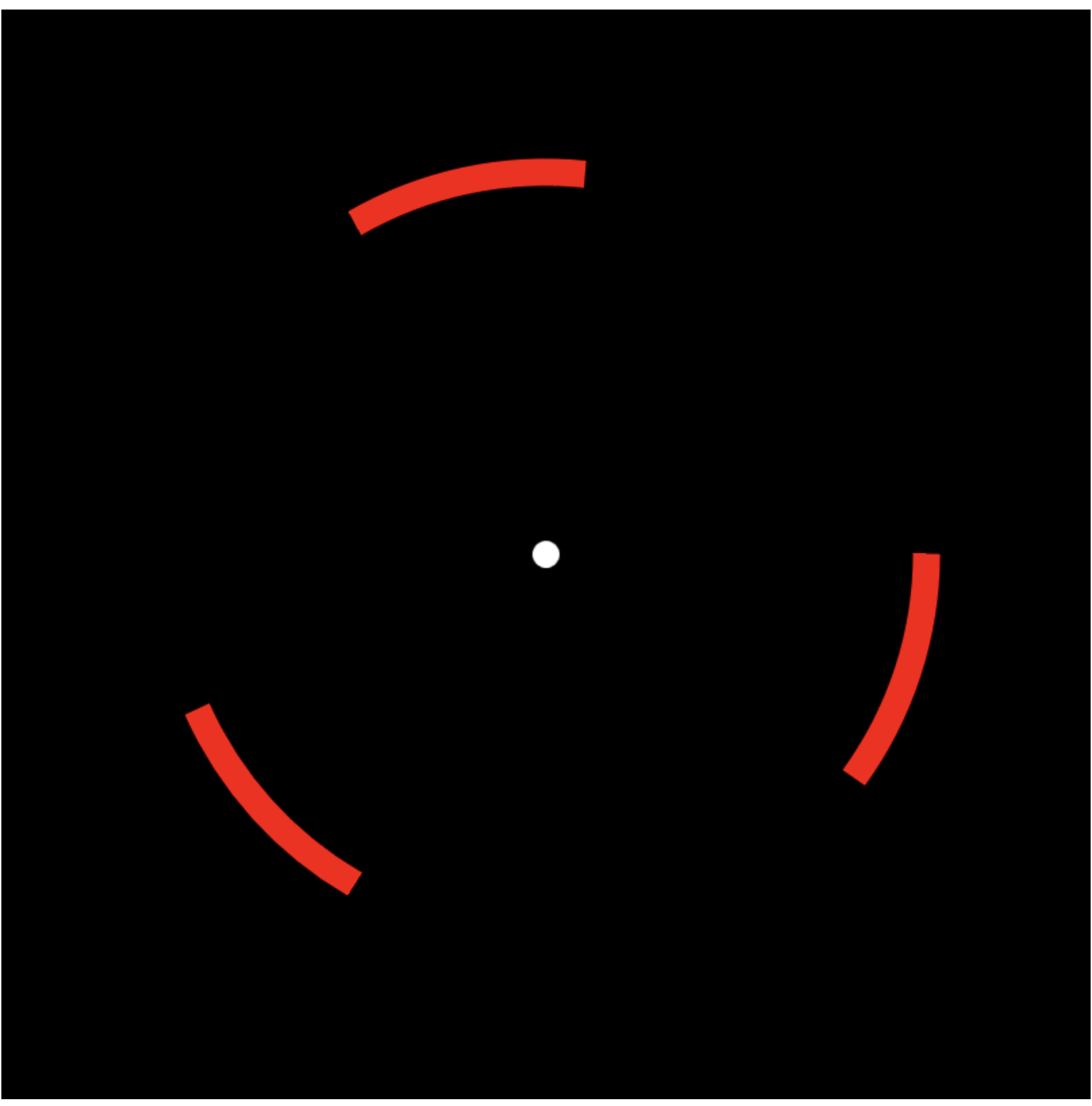

Here’s how that could look rendered : three players evenly spaced, taking 30% of the perimeter of the unit circle (hence the difficulty: 0.3 value), and a ball at the center.

I started by simply defining a render function, taking in a game struct, some viewport options, and defining a list of operations it should apply on the canvas. clear_screen clearly doesn’t need to get the game struct, whereas draw_players and draw_ball need it.

Then, those operations are transformed to commands, with the render_commands function. I then inject them into an HTML template, and open it in my browser.

def render(%Game{} = game, options \\ [width: 800, height: 800]) do

w = options[:width]

h = options[:height]

operations = [

clear_screen(w, h),

draw_players(game, w, h),

draw_ball(game, w, h)

]

commands = render_commands(operations, :html5)

rendered = Template.inject(commands, options[:width], options[:height])

File.write("out.html", rendered)

System.cmd("open", ["out.html"])

end

The template is quite simple too :

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

</head>

<body>

<canvas id="canvas"></canvas>

<script>

function runCommand(command, context, width, height) {

// ???

}

(function() {

const c = document.getElementById('canvas');

const ctx = c.getContext("2d");

const width = #{width};

const height = #{height};

c.width = width;

c.height = height;

const commands = #{Jason.encode!(commands)};

commands.forEach(c => {

runCommand(c, ctx, width, height);

});

})();

</script>

</body>

</html>

It contains a canvas, an IIFE, and our list of commands is injected into it, before being ran, one-by-one.

By filling in the clear_screen and draw_players functions, I got an idea of how those commands would look like :

defp clear_screen(w, h) do

[

{:fill_style, "black"},

{:fill_rect, [0, 0, w, h]}

]

end

defp draw_players(%Game{} = game, w, h) do

for player <- game.players do

[

:begin_path,

{:line_width, 20},

{:stroke_style, "red"},

{:arc, [w / 2, h / 2, Enum.min([w, h]) / 2 * 0.7, player.start_pos, player.end_pos]},

:stroke,

:close_path

]

end

end

It’s a bit like writing HTML5 Canvas operations, but with a leaner syntax. The differences between properties (like ctx.strokeStyle) and functions (like ctx.stroke()) disappeared, and we’re left with descriptors of the operations that should take place.

To clean up the writing style, I did not standardize on a common {:kind, [:arguments, :list]} syntax. The render_command function takes care of normalizing that :

def render_command(command, :html5) do

case command do

a when is_atom(a) -> %{name: a, args: []}

{a, args} when is_atom(a) and is_list(args) -> %{name: a, args: args}

{a, arg} -> %{name: a, args: [arg]}

end

end

On the HTML side, we get a bunch of objects describing the various calls :

const commands = [{"args":["black"],"name":"fill_style"},{"args":[0,0,800,800],"name":"fill_rect"},{"args":[],"name":"begin_path"},{"args":[20],"name":"line_width"},{"args":["red"],"name":"stroke_style"},{"args":[400.0,400.0,280.0,0,0.6283185307179586],"name":"arc"},{"args":[],"name":"stroke"},{"args":[],"name":"close_path"},{"args":[],"name":"begin_path"},{"args":[20],"name":"line_width"},{"args":["red"],"name":"stroke_style"},{"args":[400.0,400.0,280.0,2.0943951023931957,2.7227136331111543],"name":"arc"},{"args":[],"name":"stroke"},{"args":[],"name":"close_path"},{"args":[],"name":"begin_path"},{"args":[20],"name":"line_width"},{"args":["red"],"name":"stroke_style"},{"args":[400.0,400.0,280.0,4.188790204786391,4.81710873550435],"name":"arc"},{"args":[],"name":"stroke"},{"args":[],"name":"close_path"},{"args":[],"name":"begin_path"},{"args":["white"],"name":"fill_style"},{"args":[425.0,425.0,10,0,0],"name":"arc"},{"args":[],"name":"fill"},{"args":[],"name":"close_path"}];

As I kept the discipline of using the snake_cased versions of the camelCased properties of the JS side, we can roll a function like so :

function runCommand(command, context, width, height) {

const parts = command.name.split("_");

let pName = '';

if (parts.length === 1) {

pName = parts[0];

} else {

pName = parts[0] + (parts.slice(1).map(p => `${p.charAt(0).toUpperCase()}${p.slice(1)}`).join(''));

}

if (typeof context[pName] === "undefined") return;

if (typeof context[pName] === "function") {

context[pName](...command.args);

} else {

context[pName] = command.args[0];

}

}

We first convert the command name to camelCase, close_path becoming closePath, and then check if this property exists on the context (CanvasRenderingContext2D) object. If it is a function, we call it with the args, and if it is a simple property (like strokeStyle), we can assign to it.

Generating an interpreter server-side

What’s cool about that is that the rendering logic and calculations are done on the server based on the game state, and become a simple loop of draw calls on the HTML side, without computation of values on the clients. But there’s still a bit of ifs and elses, checks and string manipulations at runtime, and that’s something we could easily avoid while keeping the ease of having a simple list of commands sent to the client.

As some of the Canvas API functions are variadic, we will use a fixed number of parameters for every of them, even if that means filling default parameters on the elixir side when it shouldn’t be needed.

Let’s modify the render function to render an interpreter as the JS code to draw on our canvas.

This map goes from an operation, to a tuple containing its operation ID, whether it is a call or a property, and in case it is a call, the number of arguments it should consume. We could find a way to generate the full map from the Canvas spec, but let’s just write the few method calls and properties we use in this example.

@call_map %{

begin_path: {0, :call, 0},

fill: {1, :call, 0},

stroke: {2, :call, 0},

close_path: {3, :call, 0},

fill_style: {4, :prop},

line_width: {5, :prop},

stroke_style: {6, :prop},

fill_rect: {7, :call, 4},

arc: {8, :call, 6}

}

We then have a render_interpreter function rendering the JS function needed to run commands :

def render_interpreter() do

"""

const run = (context, commands) => {

let len = commands.length;

while (len > 0) {

const item = commands.shift();

len--;

switch (item) {

#{render_switch_branches() |> Enum.join("\n")}

}

}

};

"""

end

defp render_switch_branches() do

for {k, v} <- @call_map do

uppercased_key = camel(k)

case v do

{_id, :call, _arglength} -> render_call_branch(v, uppercased_key)

{_id, :prop} -> render_prop_branch(v, uppercased_key)

end

end

end

defp render_call_branch({id, :call, arglength}, uppercased_key) do

"""

case #{id}:

args = commands.splice(0, #{arglength});

context.#{uppercased_key}(...args);

len -= #{arglength};

break;

"""

end

defp render_prop_branch({id, :prop}, uppercased_key) do

"""

case #{id}:

context.#{uppercased_key} = commands.shift();

len -= 1;

break;

"""

end

We could have a special case for the 0-arity functions, but this gives the general idea. The script in the HTML template is modified :

<script>

(function() {

const c = document.getElementById('canvas');

const ctx = c.getContext("2d");

const width = #{width};

const height = #{height};

c.width = width;

c.height = height;

const commands = #{Jason.encode!(commands)};

#{interpreter}

run(ctx, commands);

})();

</script>

And render_commands is modified too to just output a list of command IDS and arguments, by flat_mapping over render_command :

defp get_id(call), do: @call_map |> Map.get(call) |> elem(0)

def render_command(command, :html5) do

case command do

a when is_atom(a) -> [get_id(a)]

{a, args} when is_atom(a) and is_list(args) -> [get_id(a) | args]

{a, arg} -> [get_id(a) | [arg]]

end

end

On the rendered HTML, the interpreter is renedered as a switch, consuming the right number of arguments until the end of the list of commands :

const commands = [4, "black", 7, 0, 0, 800, 800, 0, 5, 20, 6, "red", 8, 400.0, 400.0, 280.0, 0, 0.6283185307179586, false, 2, 3, 0, 5, 20, 6, "red", 8, 400.0, 400.0, 280.0, 2.0943951023931957, 2.7227136331111543, false, 2, 3, 0, 5, 20, 6, "red", 8, 400.0, 400.0, 280.0, 4.188790204786391, 4.81710873550435, false, 2, 3, 0, 4, "white", 8, 400.0, 400.0, 10, 0, 6.283185307179586, false, 1, 3];

const run = (context, commands) => {

let len = commands.length;

while (len > 0) {

const item = commands.shift();

len--;

switch (item) {

case 8:

args = commands.splice(0, 6);

context.arc(...args);

len -= 6;

break;

case 0:

args = commands.splice(0, 0);

context.beginPath(...args);

len -= 0;

break;

case 3:

args = commands.splice(0, 0);

context.closePath(...args);

len -= 0;

break;

case 1:

args = commands.splice(0, 0);

context.fill(...args);

len -= 0;

break;

case 7:

args = commands.splice(0, 4);

context.fillRect(...args);

len -= 4;

break;

case 4:

context.fillStyle = commands.shift();

len -= 1;

break;

case 5:

context.lineWidth = commands.shift();

len -= 1;

break;

case 2:

args = commands.splice(0, 0);

context.stroke(...args);

len -= 0;

break;

case 6:

context.strokeStyle = commands.shift();

len -= 1;

break;

}

}

};

run(ctx, commands);

What’s fun is that we don’t have to maintain this JS part, as it gets generated by the Elixir code.

What could be done too would be to abstract general drawing operations first, then render them to commands for the HTML5 backend, like so :

def draw_players(players, w, h) do

r = Enum.min([w, h])

for player <- players do

{:draw_arc, thickness: 20, color: "red", angular_pos: player.pos, radius: r}

end

end

def render_command({:draw_arc, options}, :html5) do

[

:begin_path,

{:line_width, 10}, # fetch line width

{:stroke_style, "red"}, # fetch color

{:arc, []}, # fetch arc options

:stroke,

:close_path

]

end

Without going that far, we can also define little functions that abstract over repetitive operations, just like clear_screen or draw_players do.

Conclusion

So, to wrap it up, these crude experiments could maybe be some ways you could render highly-expressive Elixir calls to a canvas. I think it “clicks” well with things like LiveView, where the browser can be seen as only displaying a server-side truth. Of course, you wouldn’t write an HTML file and open it every frame, but the page could connect to a socket and receive draw commands for each frame. And you don’t get inputs from the page easily.

Not for prod, but made me think on how I’d like to write all those calls to ctx.fillRect :-) .