[Talk] Code BEAM EU 23 - Prototyping a remote-controlled telescope with Elixir

Here’s a transcript of the presentation I gave on Oct. 20th 2023 at Code BEAM Berlin. The conference was outstanding, and I am really thankful for the conversations I’ve had with people there.

Thrilled to take a peek into Datalog and AtomVM for next research projects :^) .

Link to the slides (use ← and →)

Video

Transcript

Hi ! Thanks for being here and welcome to this presentation called “Prototyping a remote controlled telescope with Elixir”.

My name is Lucas, I’m a freelance who builds design automation systems for architecture companies in elixir. I’m also - that’s today’s subject - an amateur telescope builder and mirror maker, so we’ll talk about that in a sec. I mostly go by chantepierre online if you want to find me somewhere.

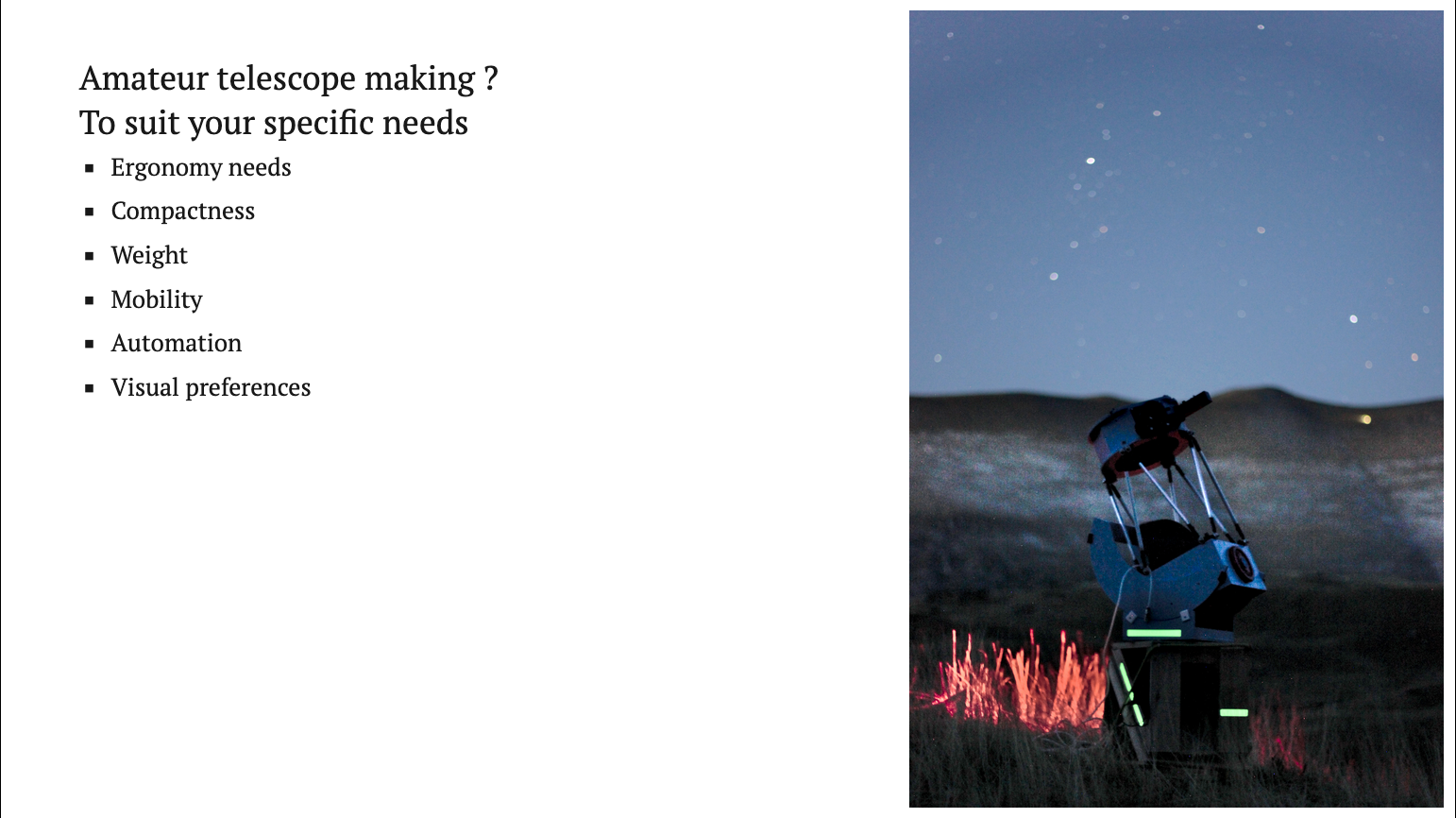

So, why do we build telescopes ? We do that to suit specific needs that have no commercial offerings. If you have some specific ergonomy needs, or visual preferences, you can build a telescope for that. For instance I like very wide low magnification fields of view on the objects I observe, so that’s the kind of scopes I build.

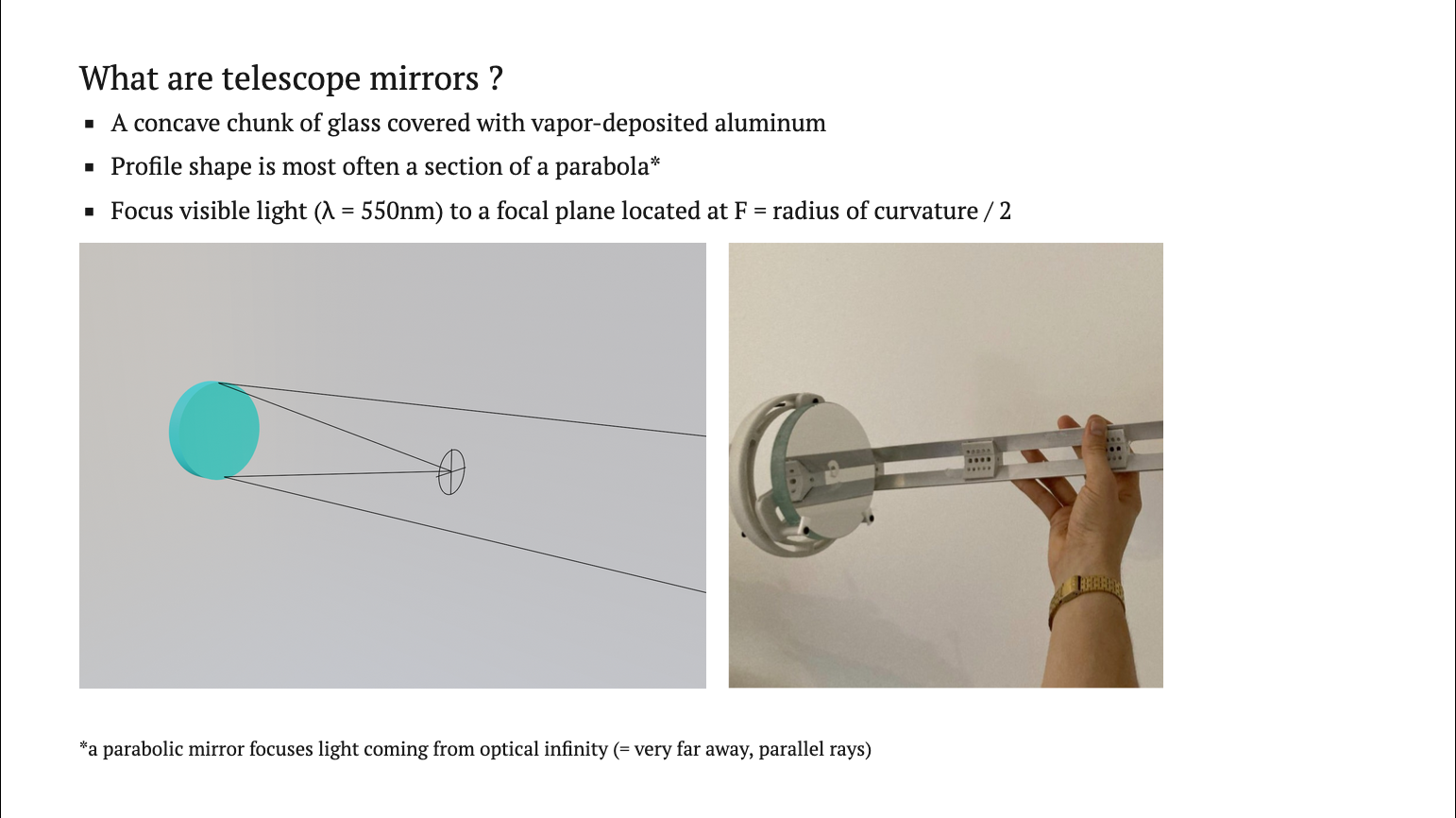

Telescopes mirrors are concave chunks of glass covered with vapor deposited aluminum, most often polished to a parabolic shape to focus light coming from Optical Infinity. So, very far away objects like the moon or stars. They can also image objects closer than that, but the image will be a bit blurry due to something called spherical aberration. This will be important in a few minutes.

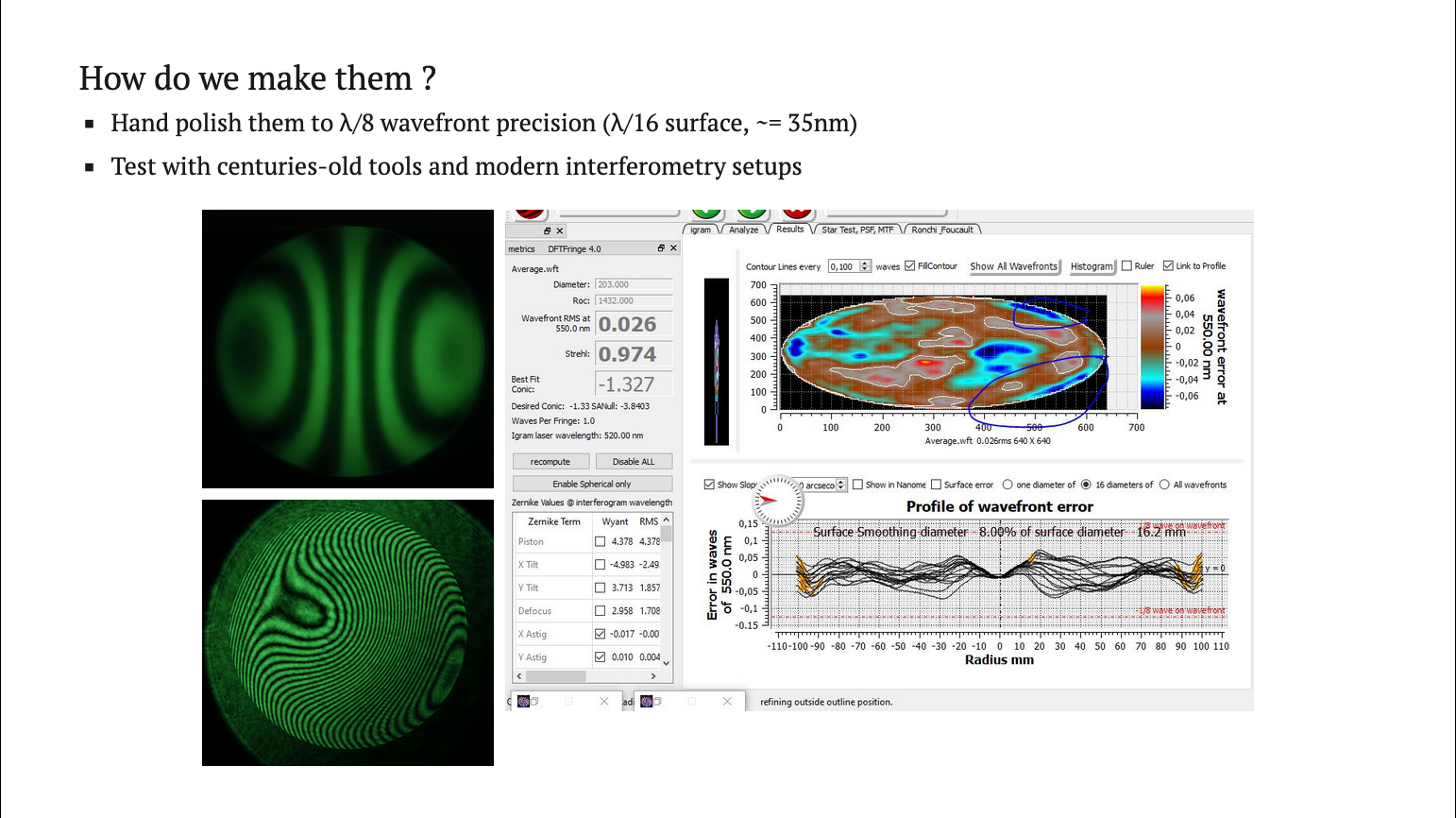

To make mirrors, we hand polish them until they reach sufficient precision like 35 nanometers on their surface. We test them with a mix of centuries old tools and modern interferometry setups, but I promised I wouldn’t talk too much about optics today.

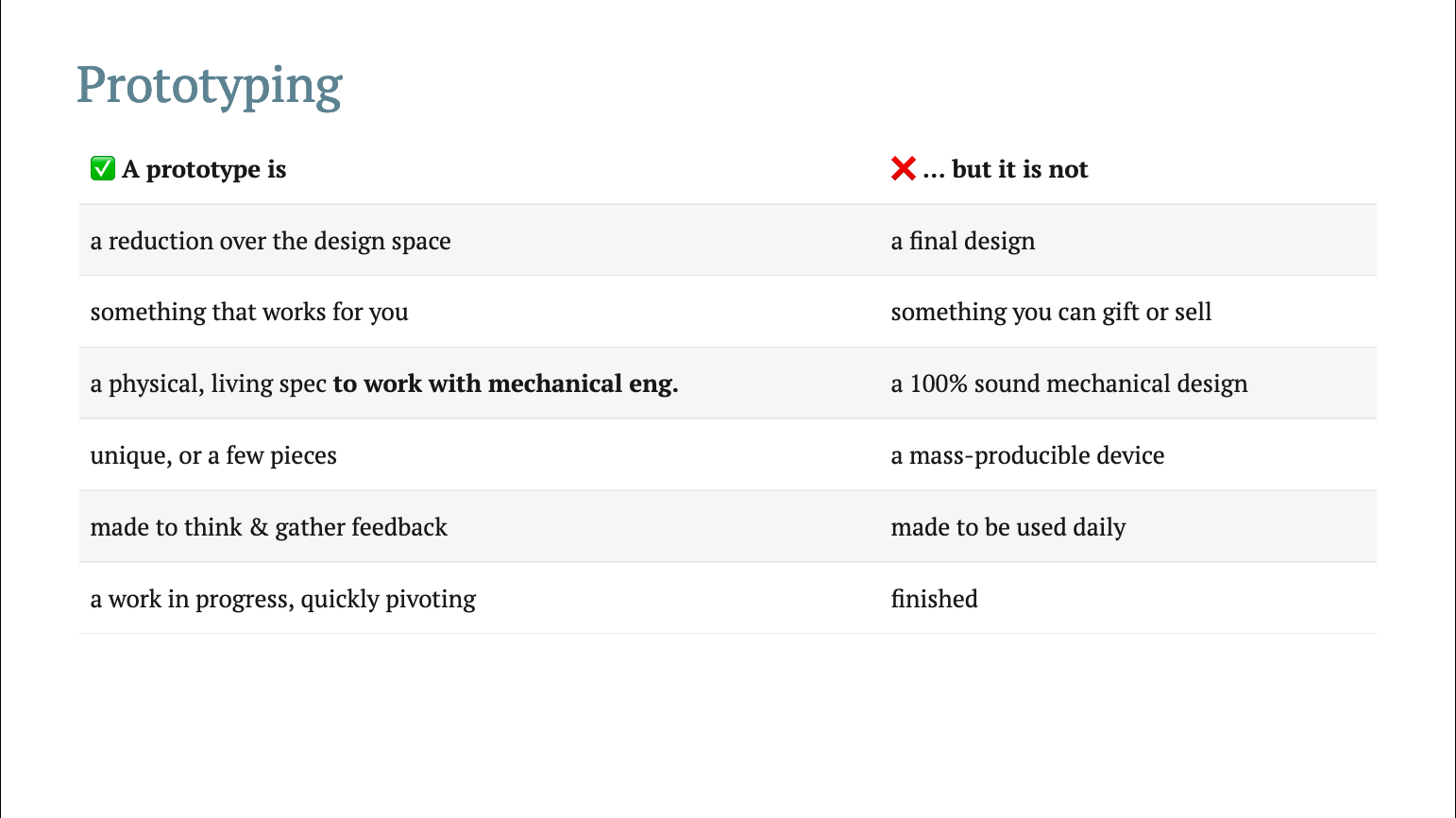

On what prototyping means for us, software developers. Maybe we cannot push a product to its full commercial completion, but that’s okay we can totally build something functional enough to have a living thing, to take it further with engineers. Or something maybe that’s polished enough for our own personal use.

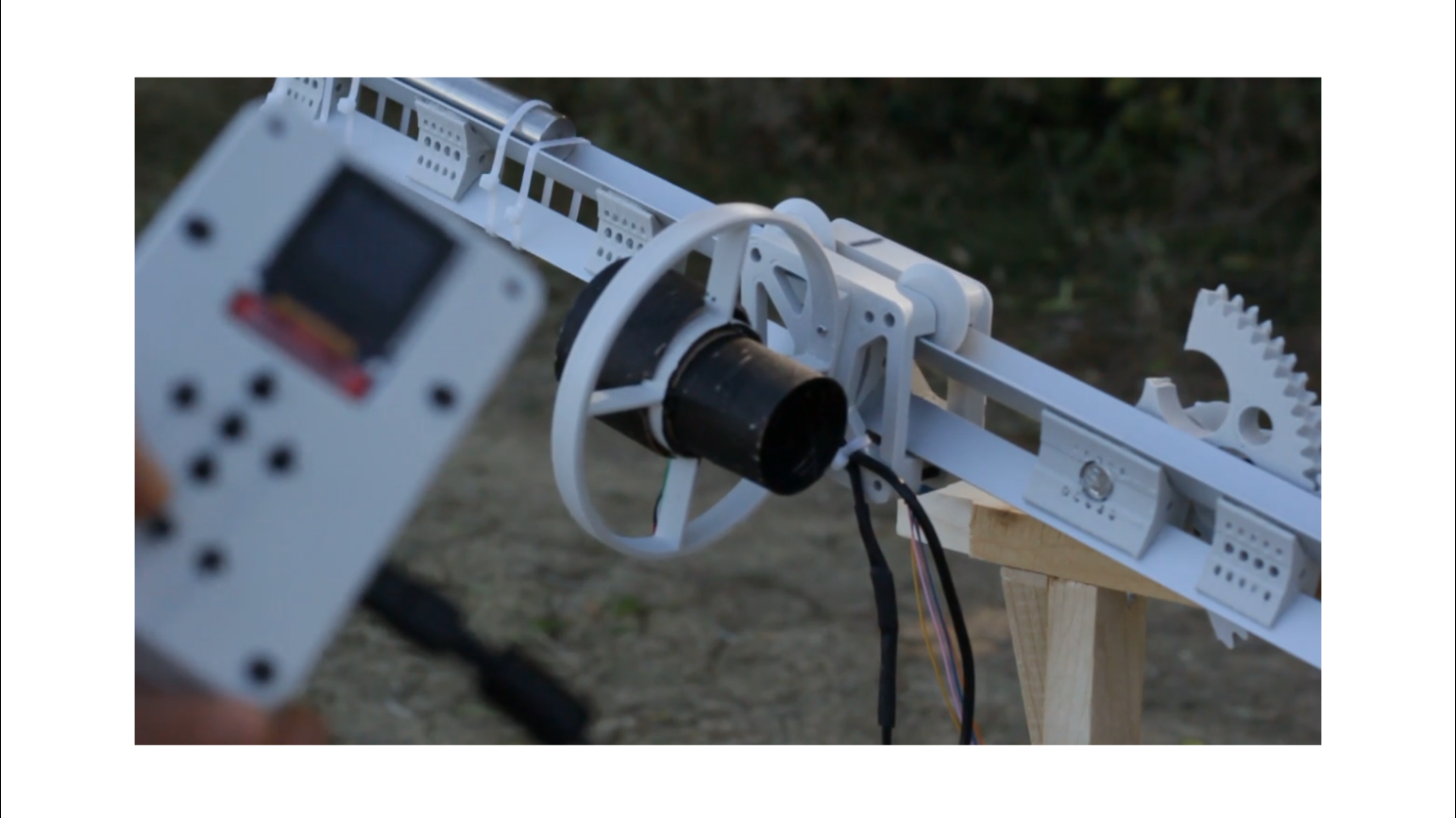

A quick overview of the physical project : this one is special because it’s a terrestrial telescope. I made it to look at birds, trees, and nearby objects, so not space related things like my other builds.

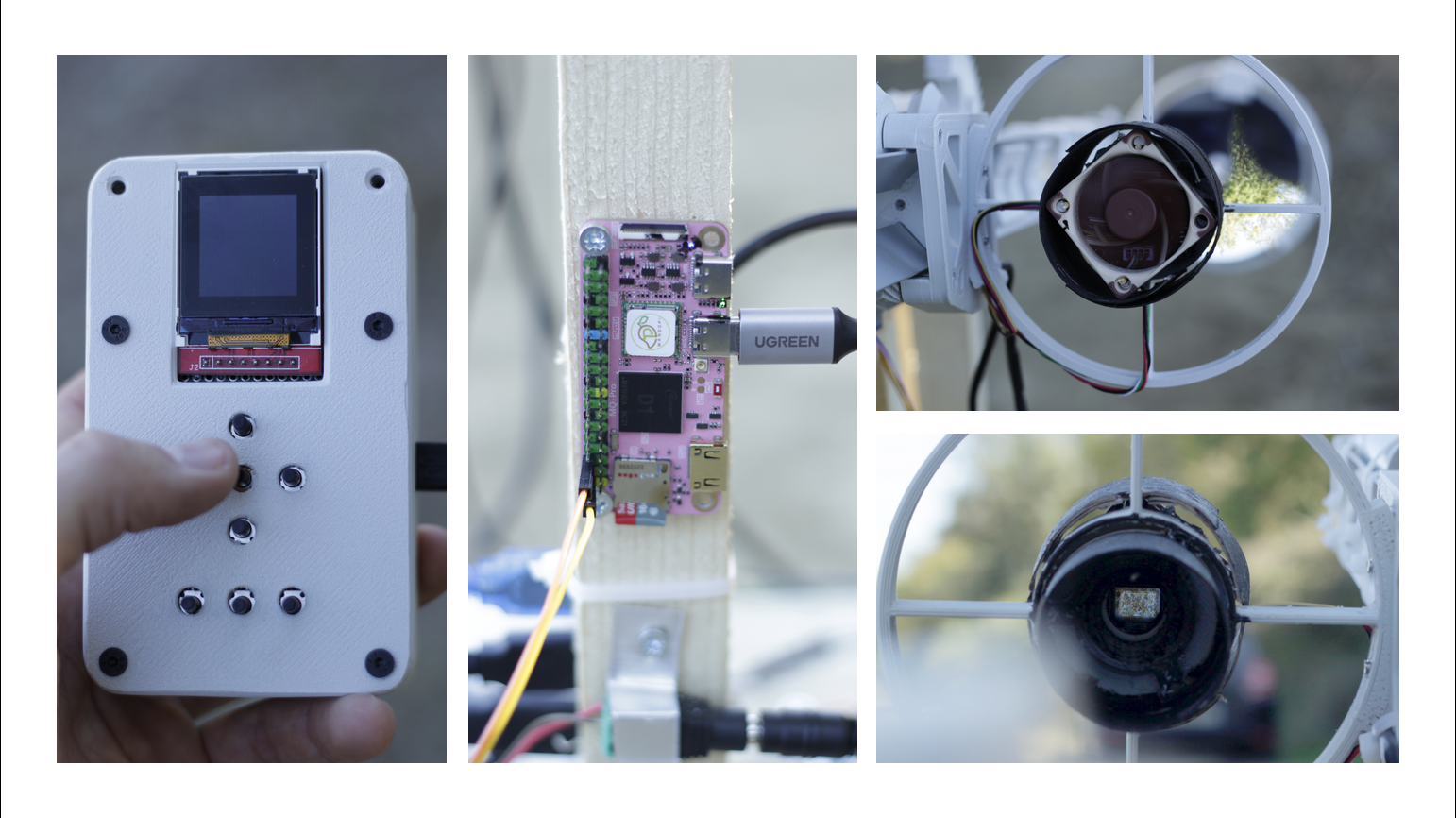

It’s a single arm design that moves in altitude (so, up down) or azimuth (left and right). Here I’m controlling it with my smartphone, you can also see why I didn’t bring it - like you can’t really bring that on a plane.

It focuses the image by moving an upper sled where the camera sensor is located, and here I’m controlling it with a physical remote control. So there are two ways to control it, one with a live view app, and another one with a physical remote control.

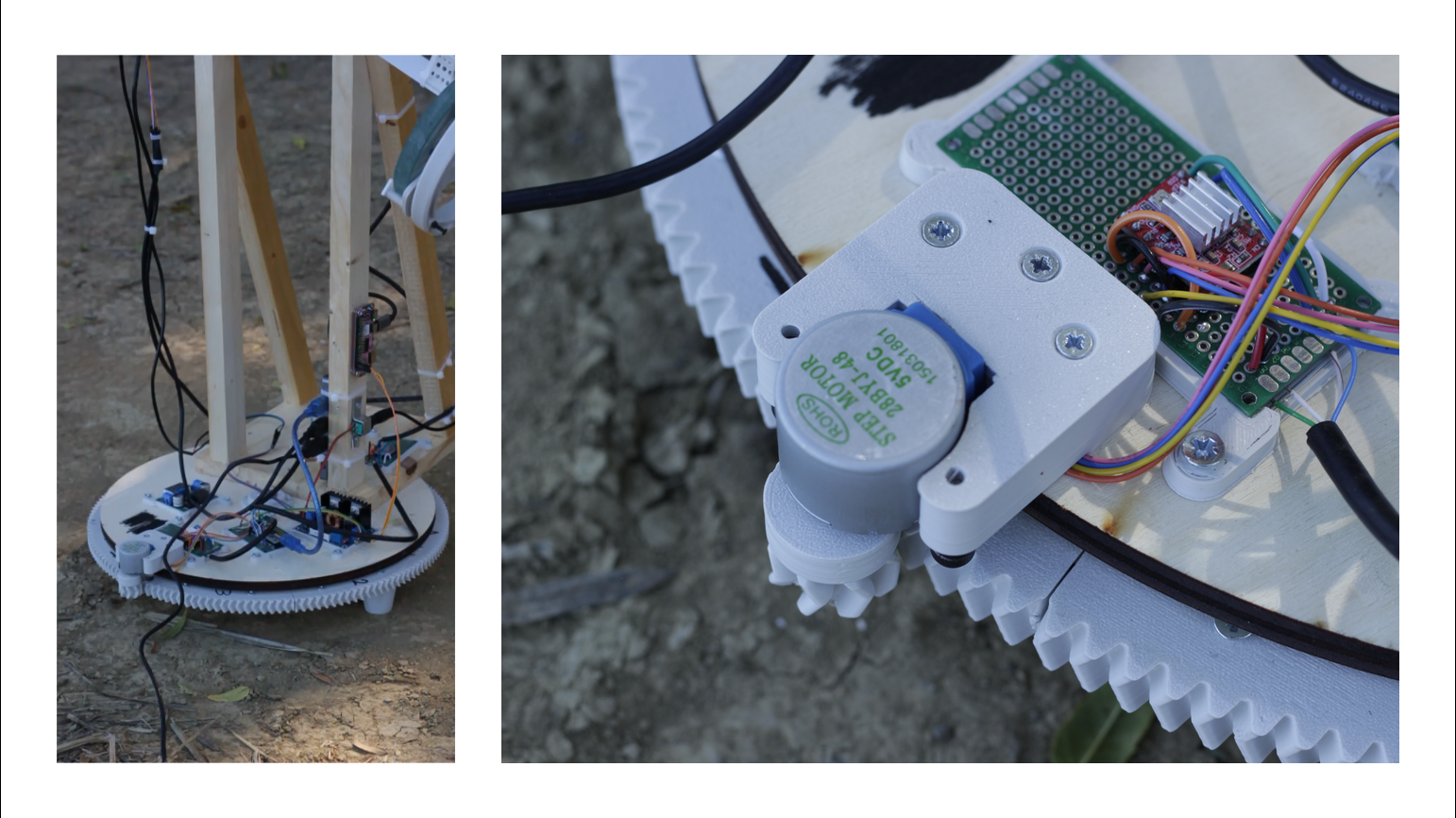

Here it’s driven by those cheap and ubiquitous 28 byj Motors - I tried to only use components that I had on hand, and not buy anything new because it’s a first draft, so it will evolve into something else. I also 3D printed a lot of parts.

Left to right : the remote control, the Mango Pi which is a 1 GB Ram 1 GHz single core RISC-V SBC who runs the nerves app. On the upper right you can see the mirror seen from the upper cage, and on the lower right you can see the image of a tree focused on the sensor. The image has a physical reality at focus and we can see it here.

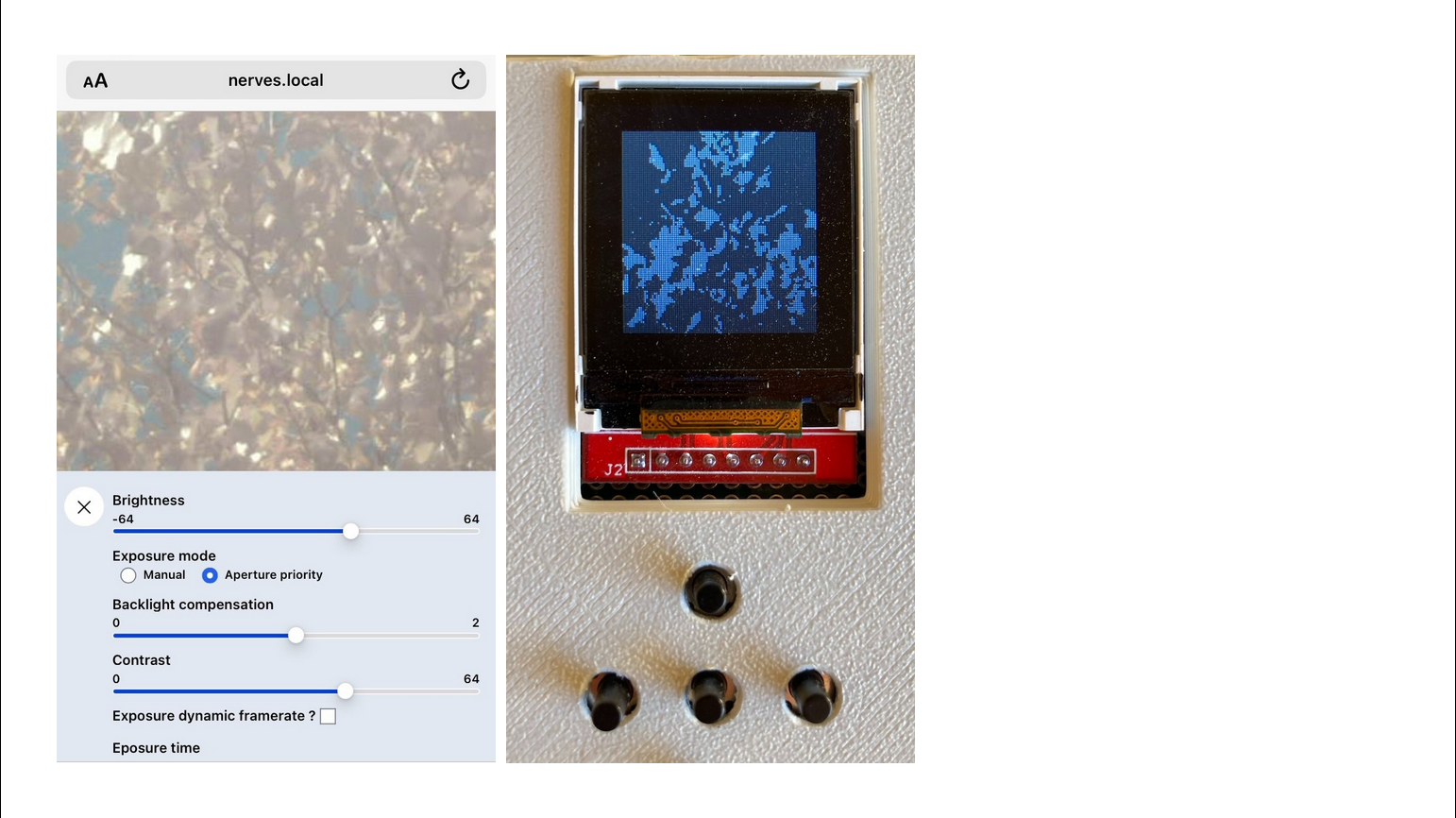

On the left, there’s the capture UI as seen on my phone, and on the right there’s the image streamed in 2 bit gray. We have four color levels, and it’s cropped to 100 by 100 pixels for the remote control.

So, how do I tackle this kind of projects ?

I like to start with simulations. My primary work is software, so it’s a great

sketchpad. I start in the REPL, mainly Elixir, then I move to little simulations apps.

This allows to think about realistic IO. At some point you have to quit those simulations and build the

real thing, but it’s a good first step. I’ve started to use LiveView for that too, it’s really a nice tool for

that.

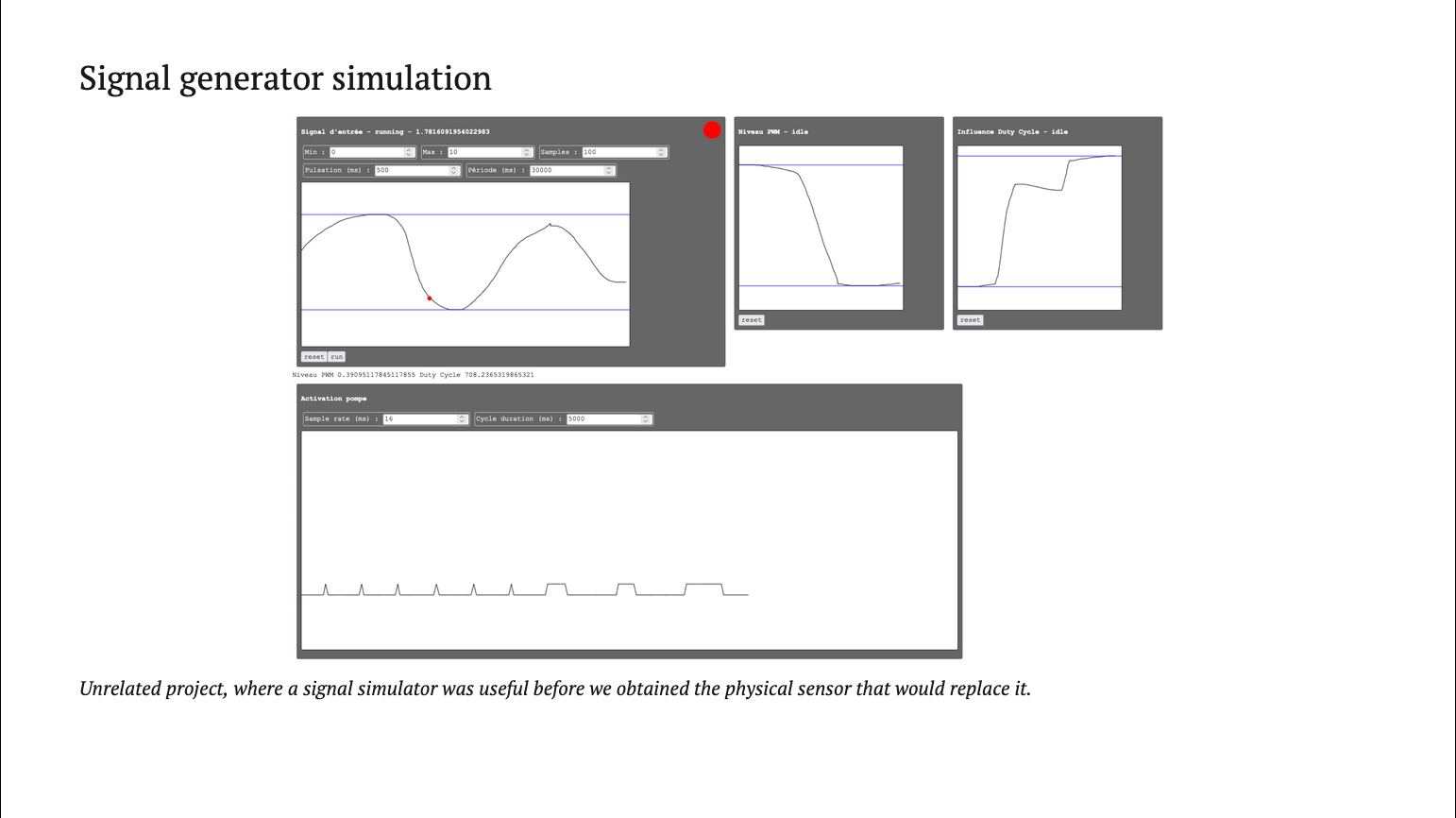

Here’s an example of a signal generator for another project with Nerves where we didn’t yet have the physical sensor that we would use at the end. You can totally simulate some kind of device, and plug that into your software while you wait for the real thing to exist, and it should work. And indeed, it did.

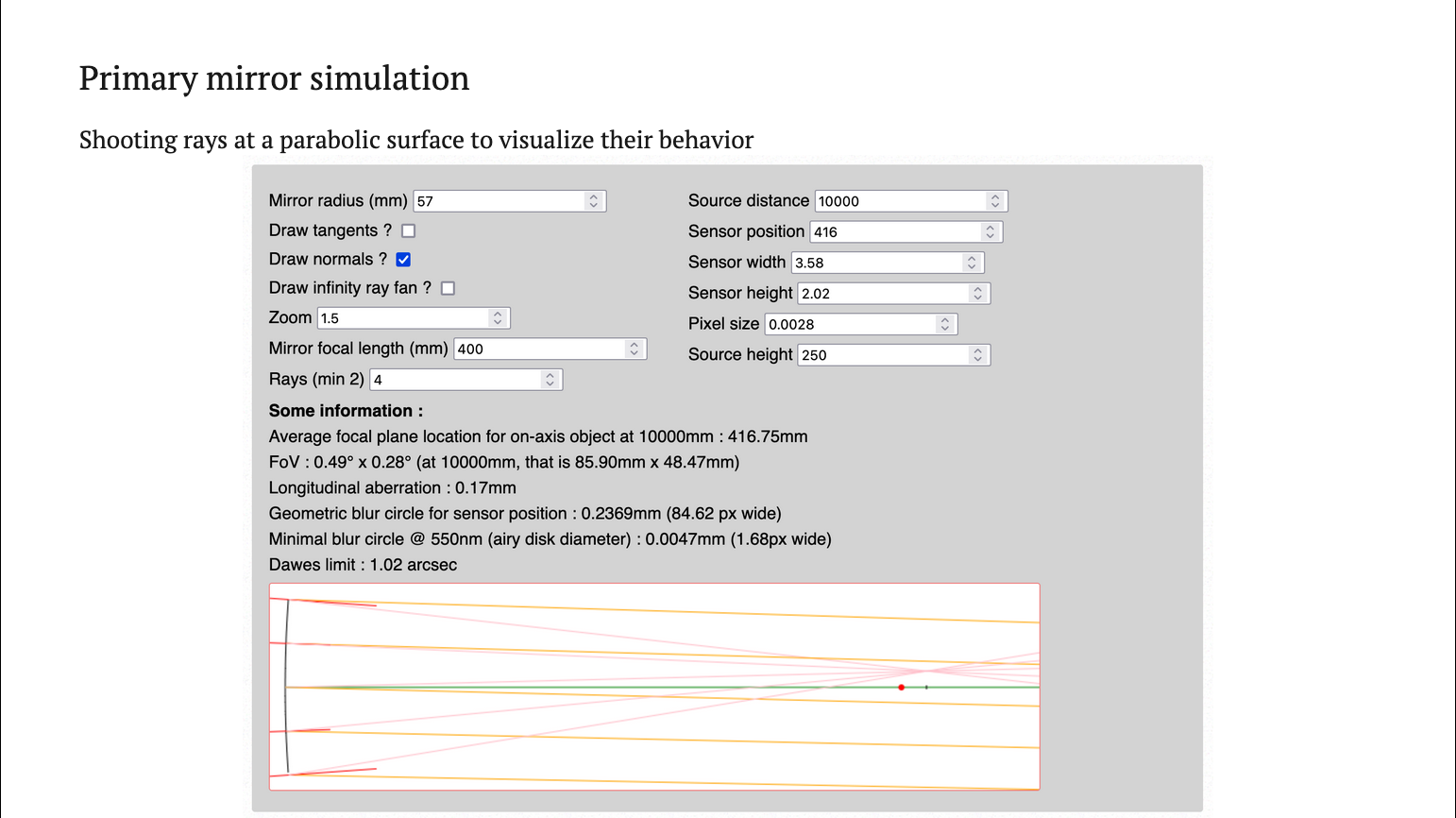

For this project, I started with little JS applets, like raytracing a parabolic mirror. I don’t have a math background, so this is my way to get through the weeds and understand things at an actionable level.

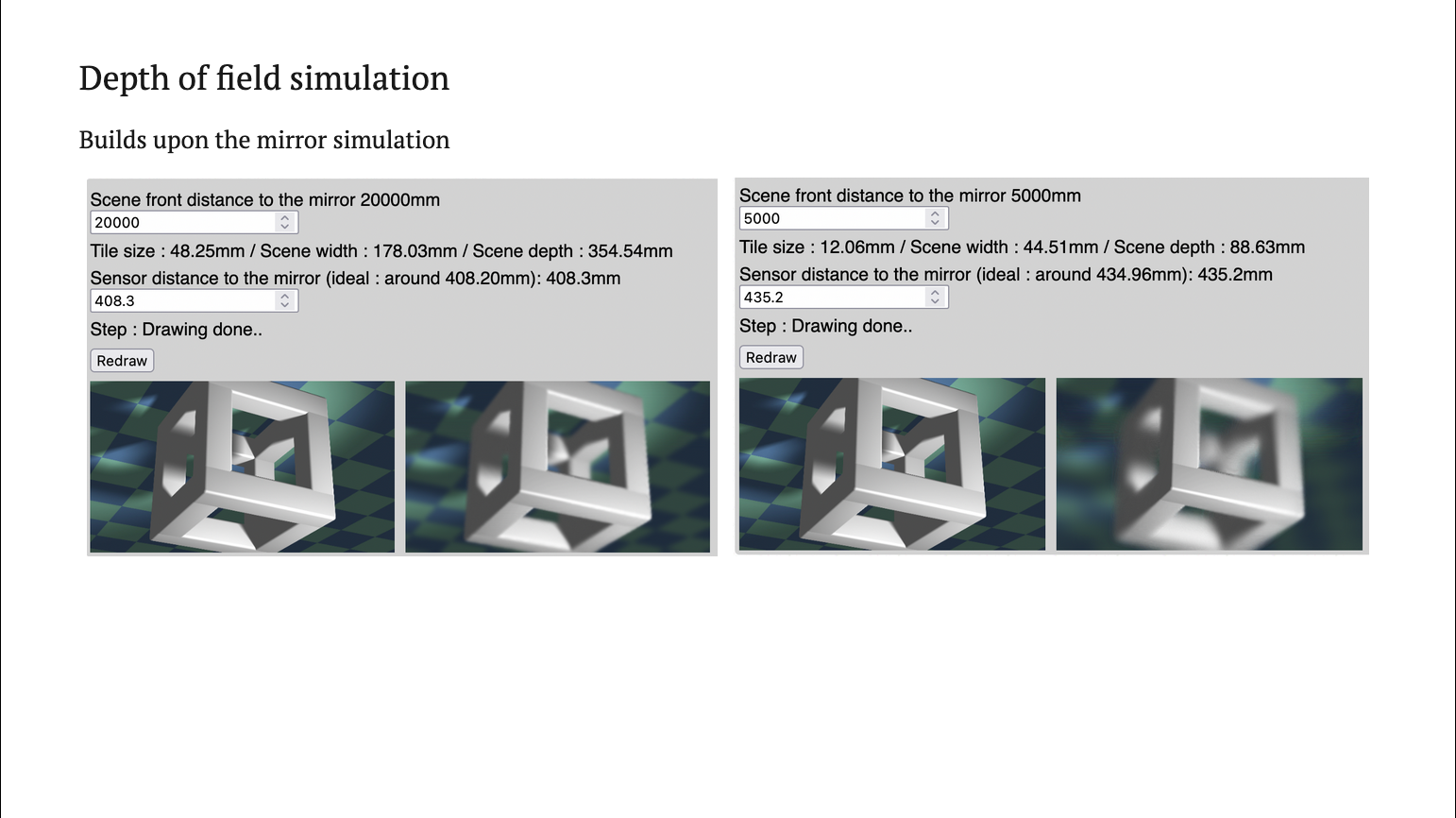

Building on that simulation, I was able to build a depth of field simulation. You can see the depth of field changing with regard to the object distance for the specific mirror I’m using. All of that was in JS and it has been ported later to Elixir and Rust for the image calculation part.

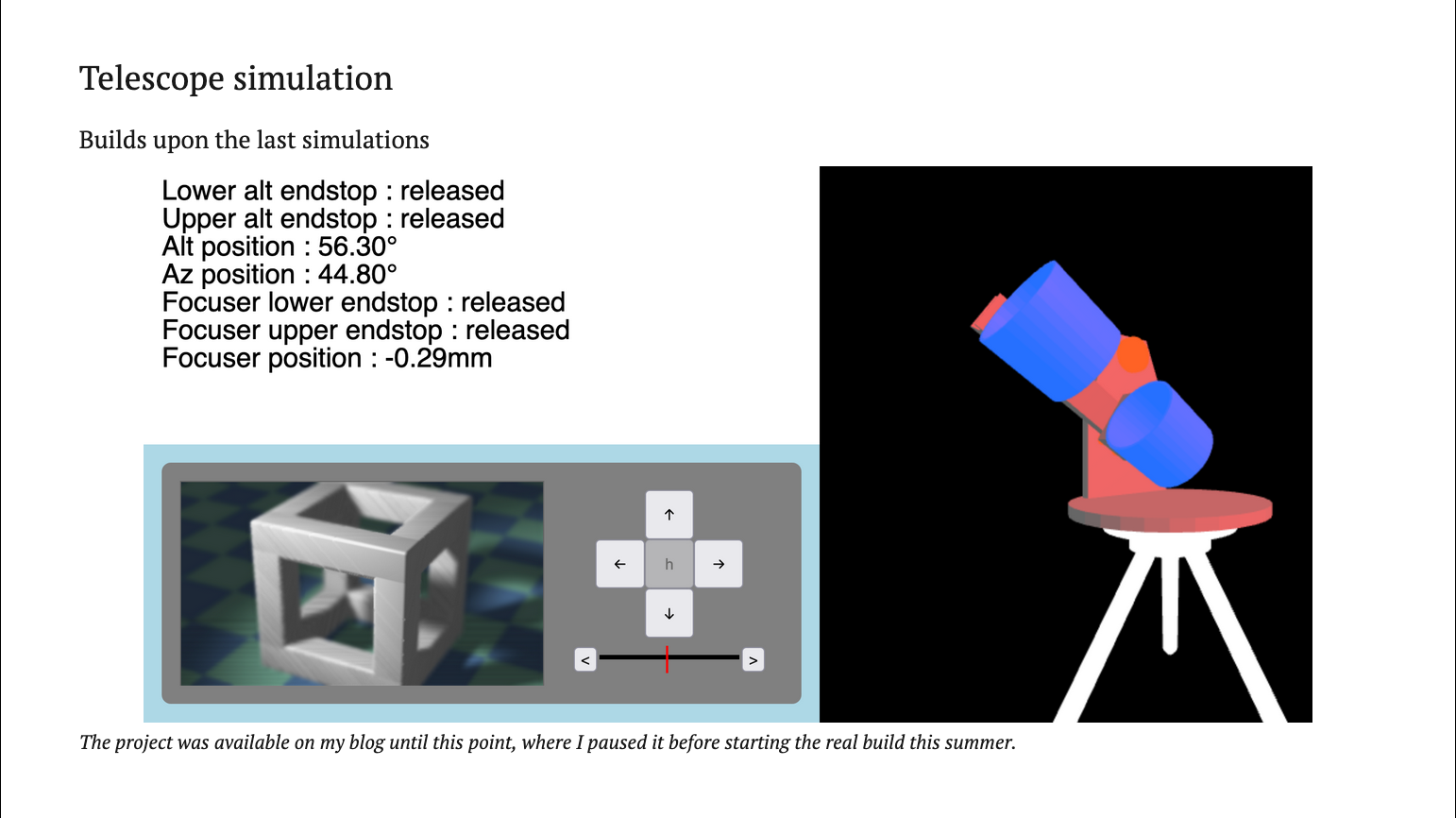

I then reached a simulation of the complete system, like you had a moving 3D telescope. Its state was displayed and you had the the virtual remote control with left, right, up, down, and the focusing range.

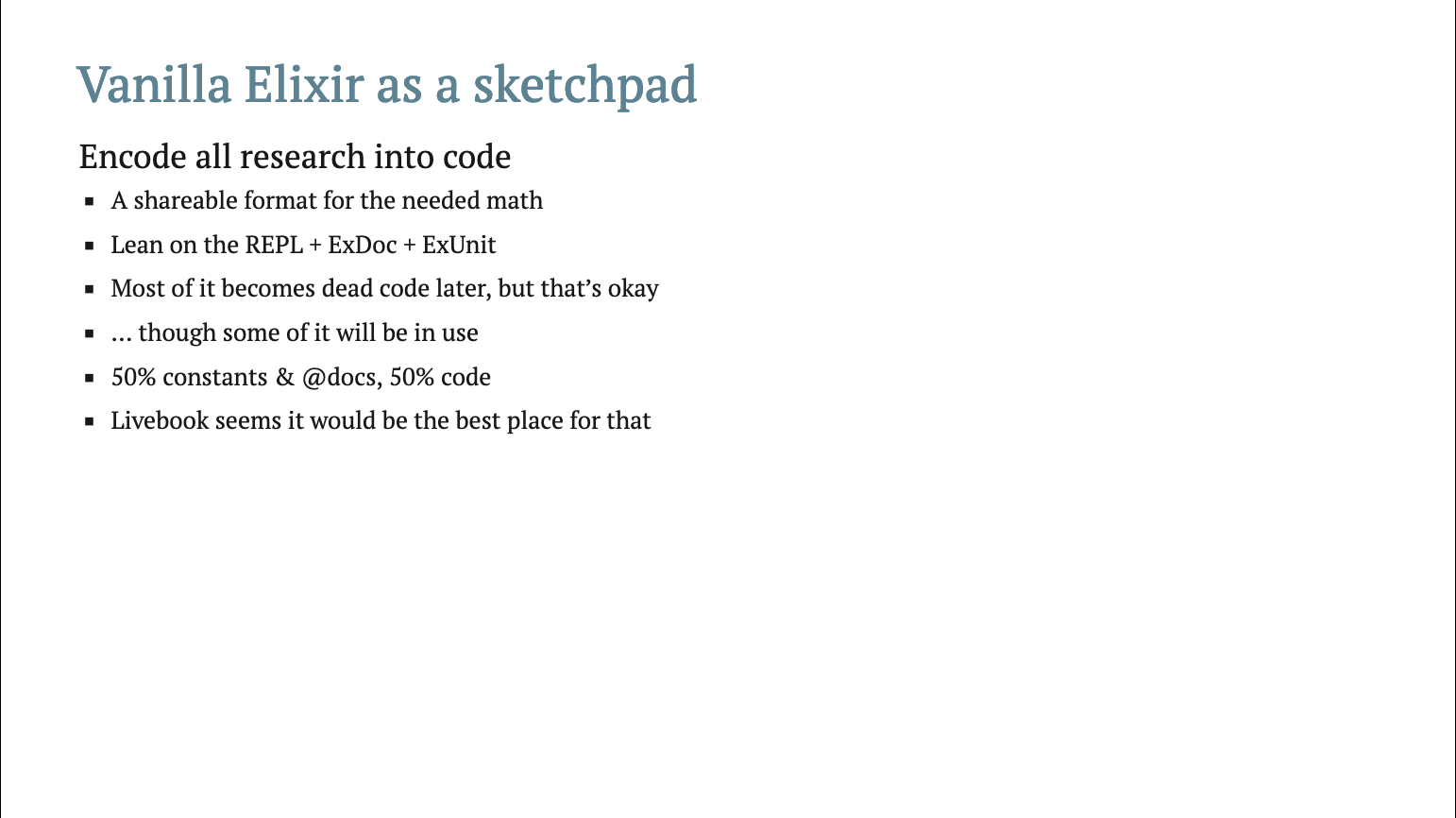

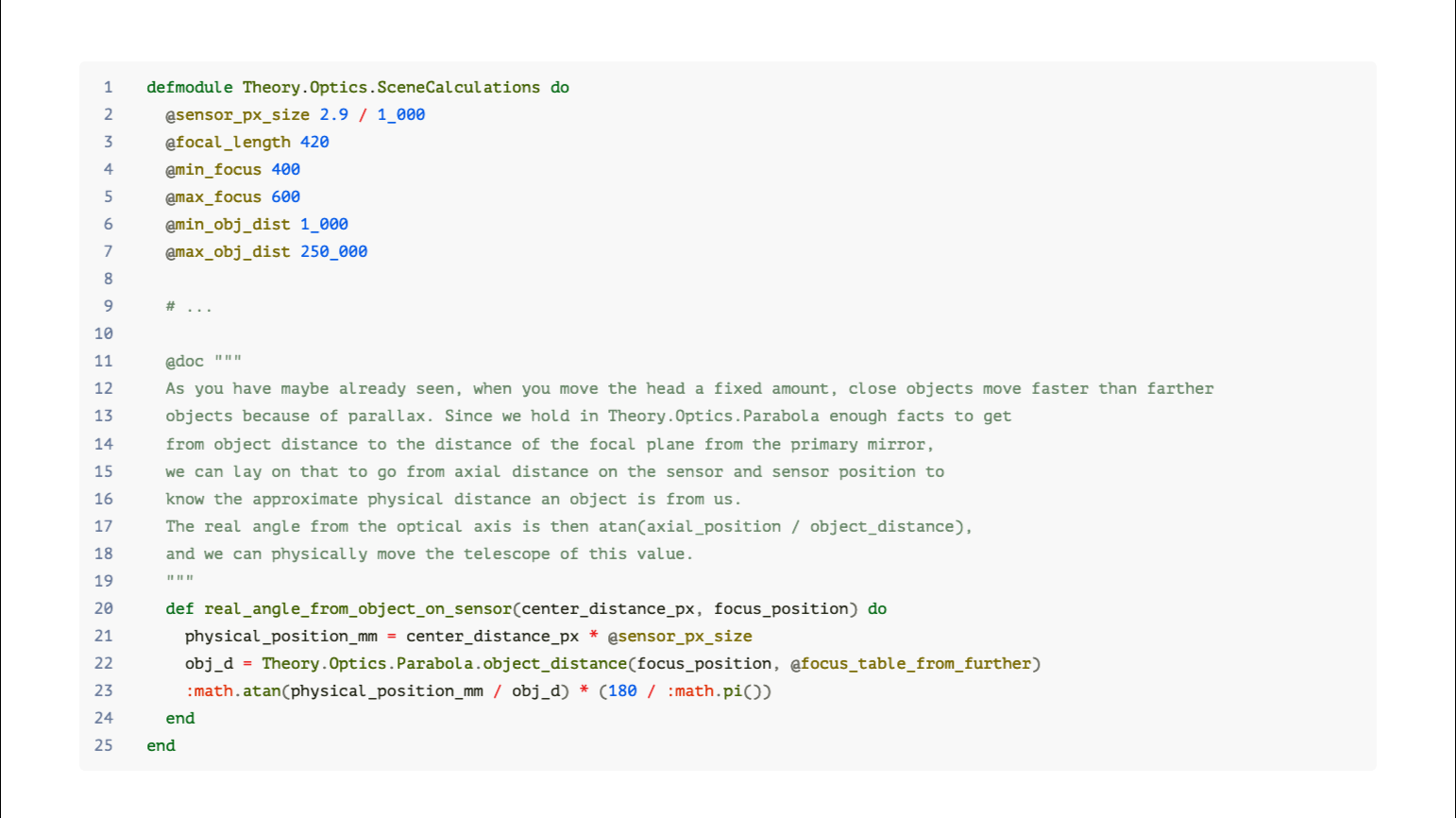

When I start the Elixir part of those projects, I try to take all the facts that I will need (so equations, formulas, papers) and I try to understand them one by one by implementing them in code. I add long @docs and sometimes even doctests that show their numeric results. They have no real value as tests but those modules make a great cheat sheet to come back to later.

That’s an an example of that kind of module. All code will be approximate because I shrinked it for the presentation, but you get the general idea: lots of constants, lots of docs, very little code. It’s like executable blog posts or something like that, and I’m trying to move to Livebook for that kind of thing.

I also like to introduce Rust quite early in the mix, because there’s often some numerical part that can benefit from a hot loop. Like if you have some number crunching, grid calculations, or operations on pixels or images. If you never used Rust before, the Rust compiler feels like you have a buddy to program with. It’s very friendly and comprehensive, it’s a great developer experience. Beginning to use it from Elixir requires very little setup and ceremony thanks to Rustler.

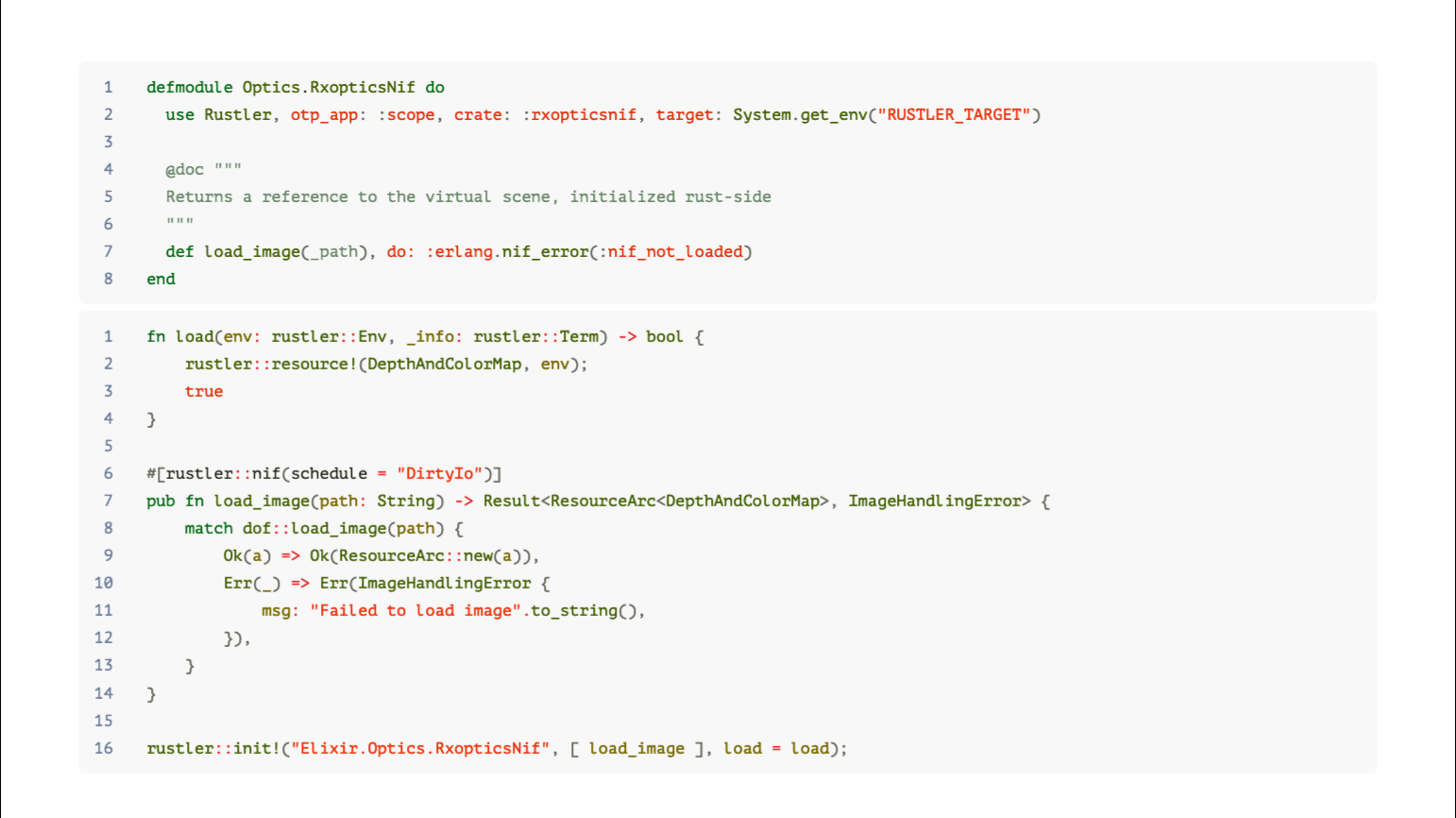

Here’s the setup for a simple NIF in Rust with Rustler. You can see a Rust function here that returns an Atomic Reference Counted resource to an image that has been transformed, and then when you have this reference on the Elixir side, you can pass it around freely between Rust and Elixir. It’s kind of handy. Rustler also allows you to annotate functions with the kind of dirty BEAM scheduler to use. If you know that your function will take more than a millisecond to execute, you should put it on a dirty scheduler. There are CPU bound dirty schedulers and IO bound dirty schedulers. This is BEAM functionality.

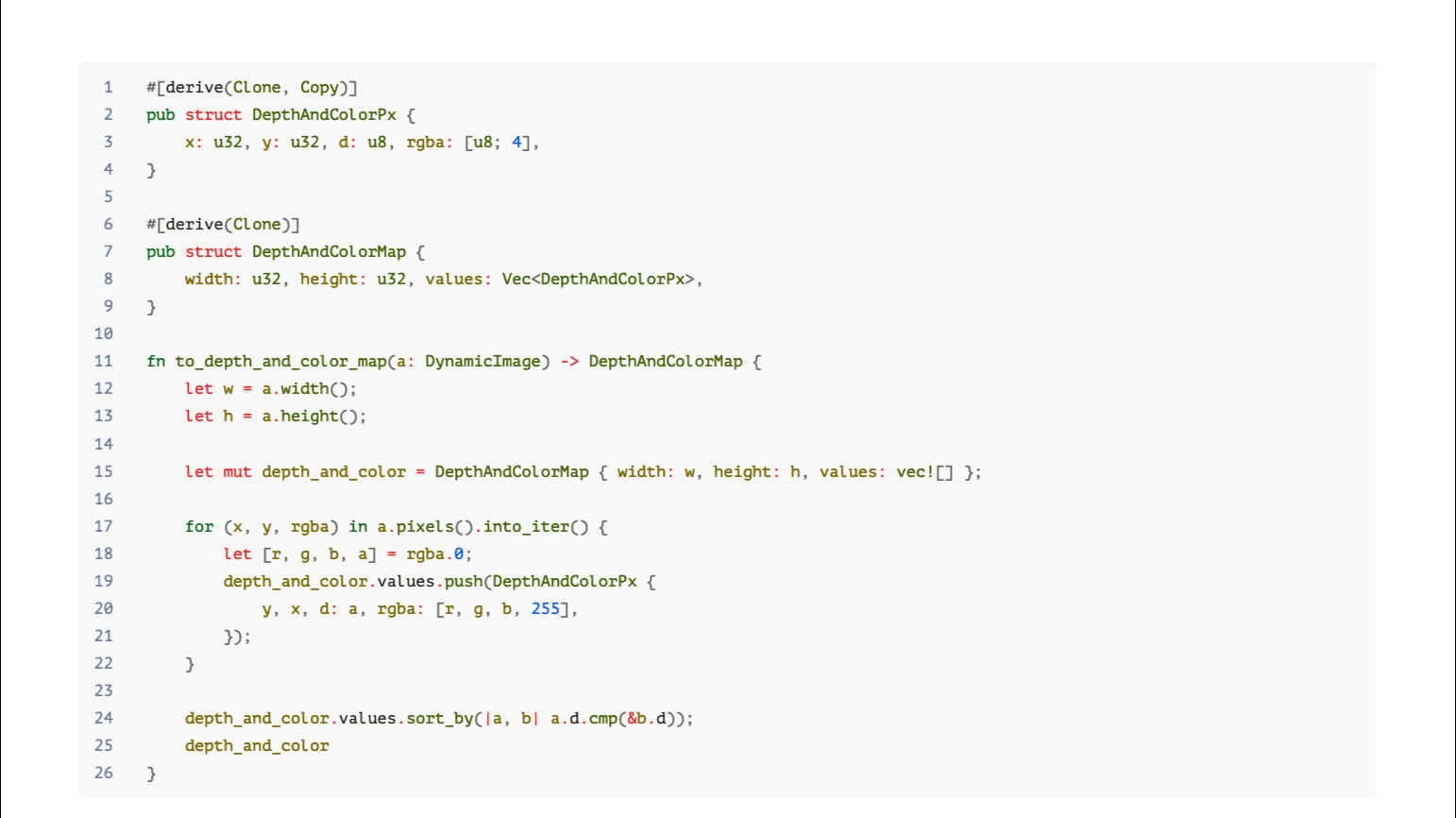

Some more simple Rust code, just to show that it’s quite readable even if you don’t know the language. There are some structs, some function taking a DynamicImage, working with a loop on the pixels and returning an instance of my struct. It’s quite straightforward if you treat like only pure functions, you don’t really have to fight with the borrow checker. But you’ll eventually come to it, it’s maybe a cliff, but you can climb over it.

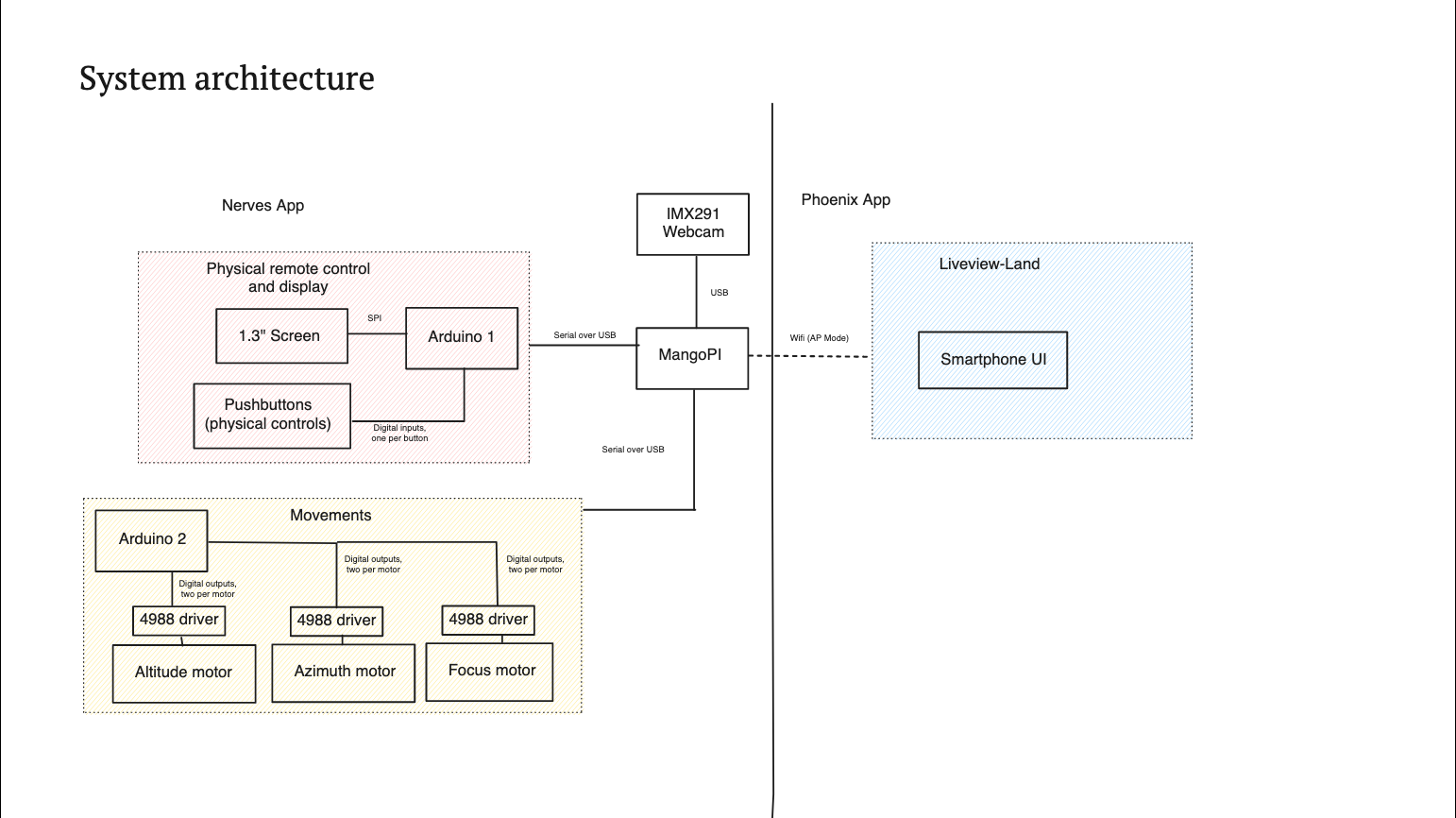

So the complete system : the Mango PI is at the center, connected to the IMX camera. There are two parts handled by Arduino Nanos : the physical remote control and display part, and the movements part, which has a second Arduino. Both are connected via serial over USB, and the Phoenix app is handled by LiveView. You access it by Wi-Fi because the MangoPI goes into AP mode, so it emits a wireless network.

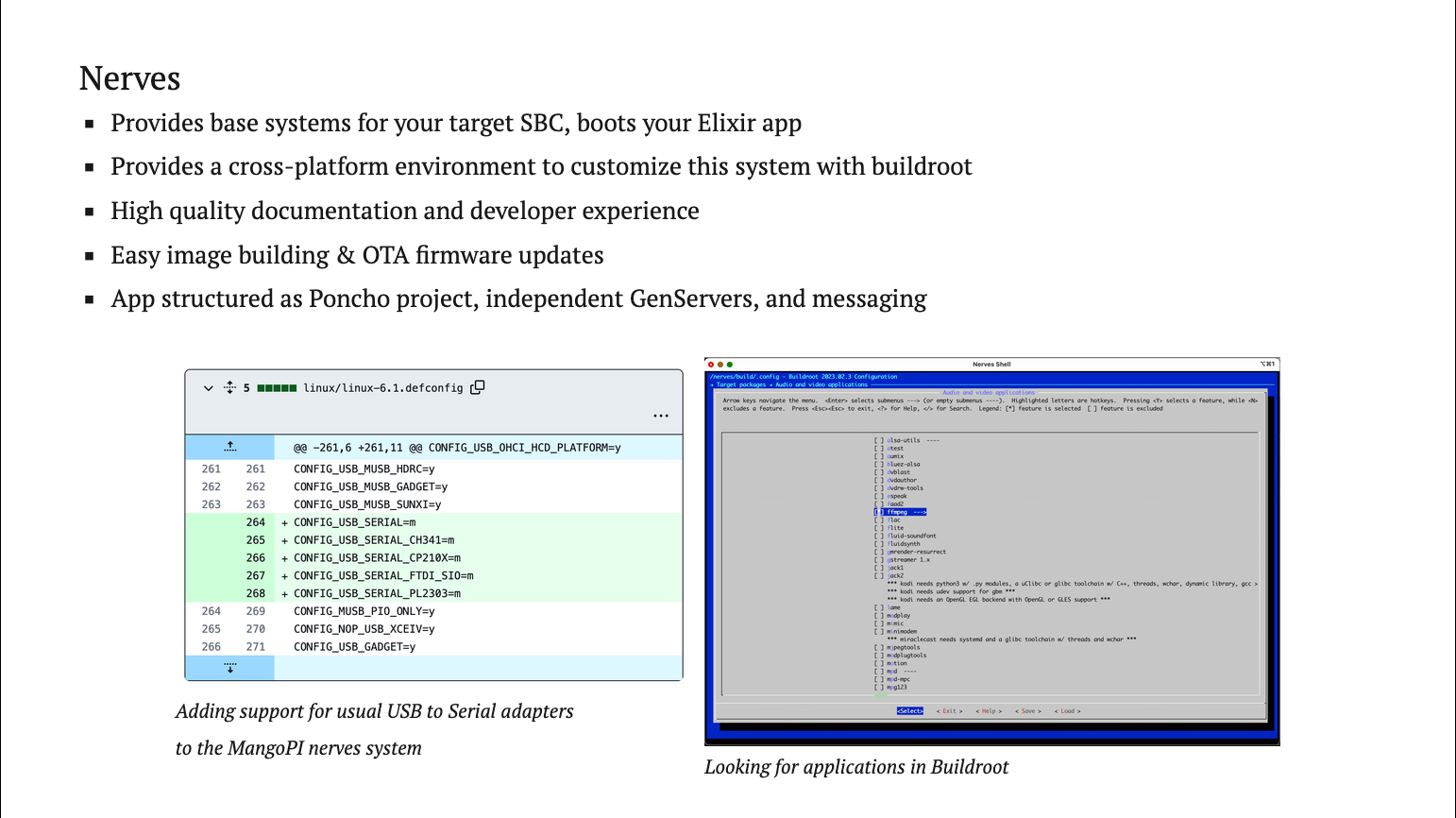

This was my first Nerves experience - it was really smooth, cross-compilation is a non issue, you just forget it. I only blocked on cross compiling my NIF from my Mac, because it needed C libraries for Video4Linux, which is not on my Mac. Nerves also gives you a working environment for working with buildroot, which allows you to add device drivers or some applications to your your base Nerves system, and the whole experience felt very batteries included. I also submitted some documentation PR to Nerves and a tiny hardware support PR to the Mango PI base system, and maintainers were really open and welcoming, so thanks to them.

Just a screenshot of the tricks Nerves pulls to allow you to use buildroot, it generates a command for you to go inside a Docker container where everything just works.

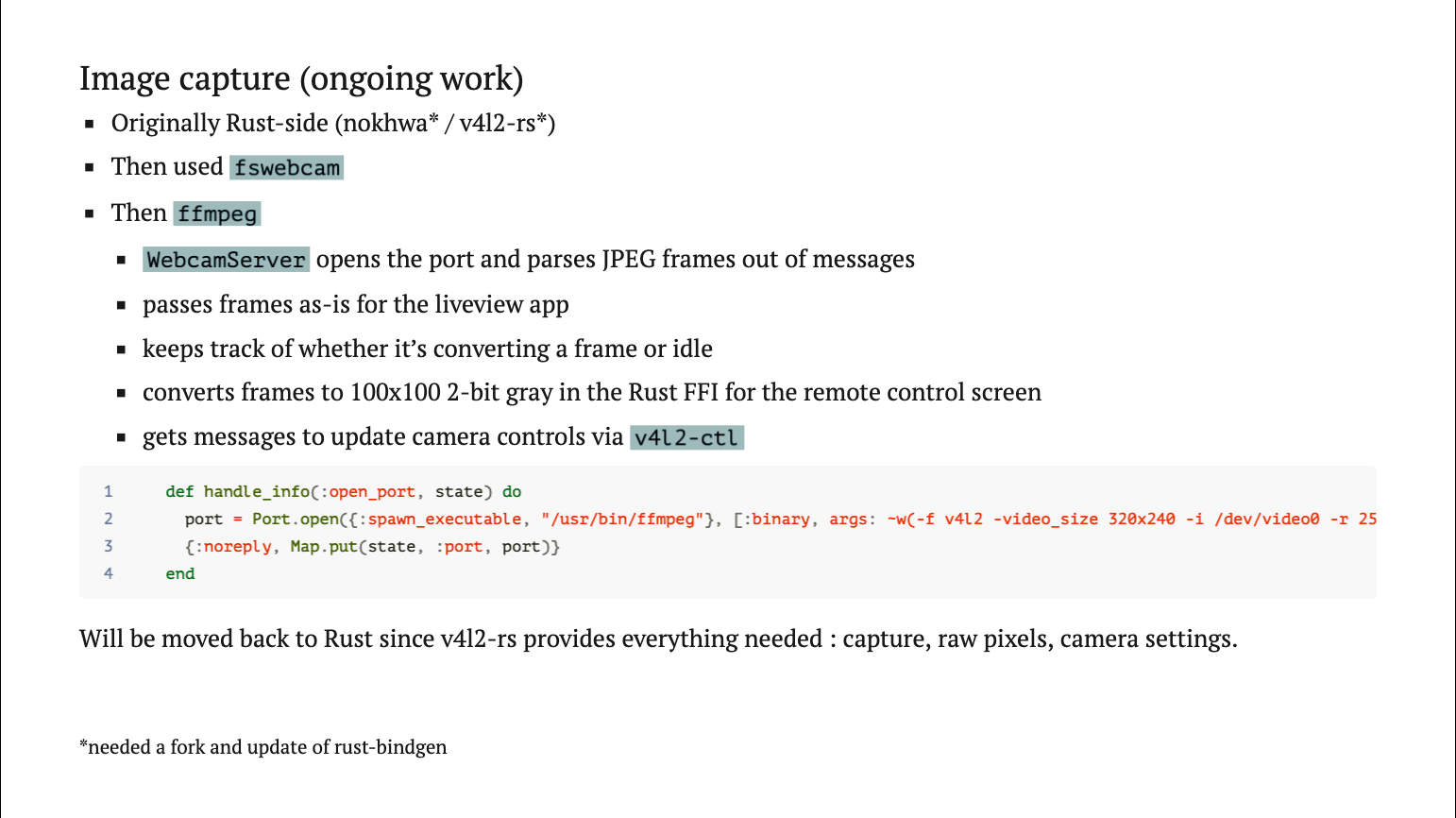

Image capture is still an ongoing topic. For now I just open FFMPEG in a port, who emits jpeg frames that are sent to the LiveView UI that paints them. The LiveView UI emits messages to update camera controls, which are passed to the camera by shelling out to V4L2-CTL. Eventually I’d like to finish that part in Rust because v4l2-rs provides everything needed, from the capture to the access to the raw pixels, or camera settings. This would be a better dev experience.

For serial communication, Nerves provides everything needed in the Circuits library. The general workflow is that you open a Serial Port, you configure its framing, so the boundaries of the messages, you put it into active mode and then transfer its control to a specific process. In my case, I have two Arduino Nano, they share the same device ID, so they just emit discriminant bytes, until the Nerves system picks them up and re-attributes them to the correct process.

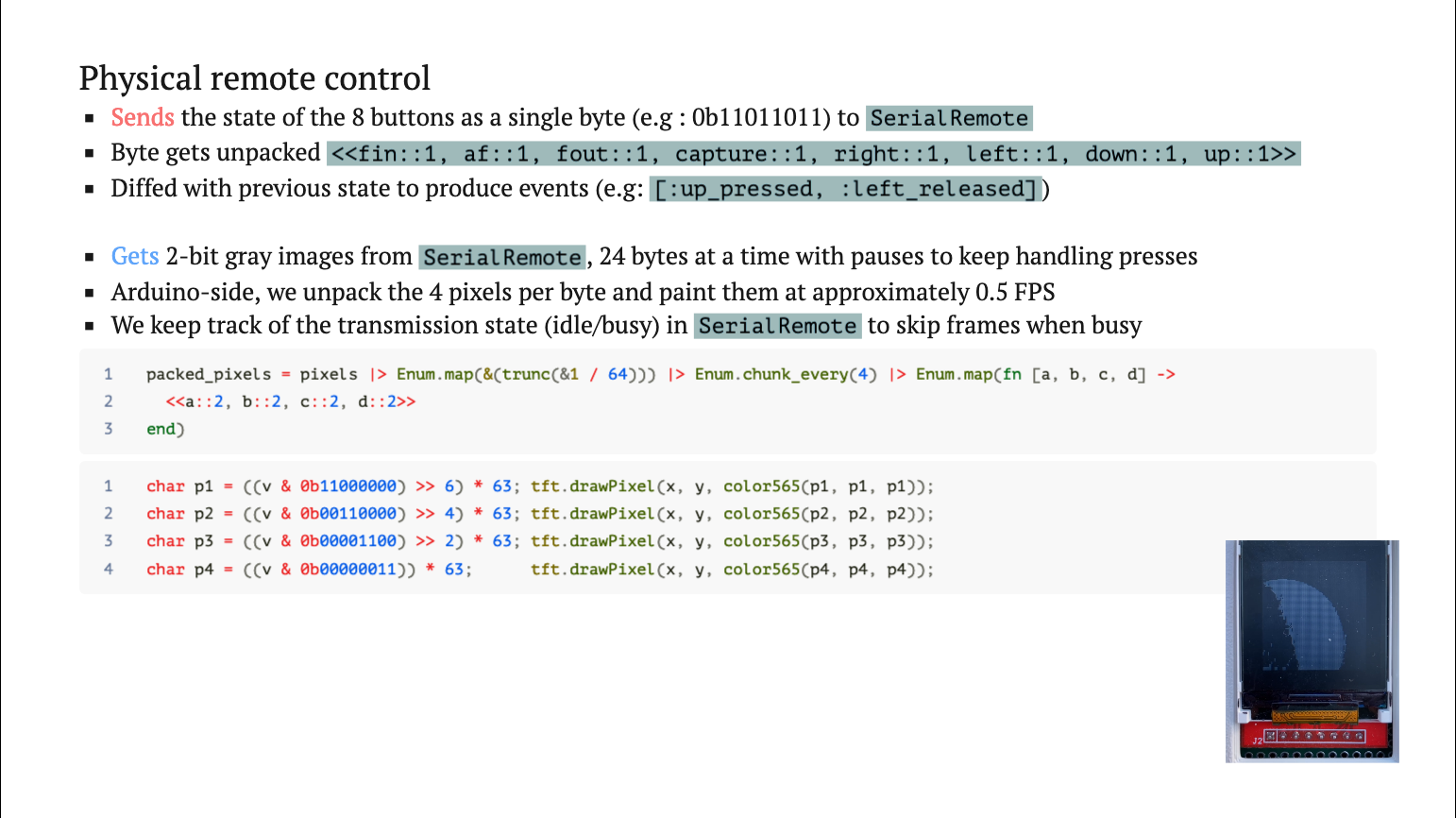

My protocol is quite basic: the remote control emits the buttons states packed as a single byte. I have eight buttons, eight bits, this matches well. It sends them to the Mango PI. On the Elixir side I just explode that with pattern matching, and there’s a GenServer that is tasked with diffing that with the previous state, to produce events. The LiveView UI produces the same events.

On the other side, I send packs of 24 bytes. Each byte in this payload represents four pixels because I work in two bit gray, so I have two * 4 bits in each byte, and this size of 24 bytes by message was found to keep the controls responsive. Because I stream to the remote control, but I can still press the buttons, and on the lower right, you can see the arduino struggling to paint frames on the remote control.

That’s the moon, moving from our perspective in the sky, and we’re at like 0.5 FPS. So draw calls are very expensive on the Arduino and I will move that part to Elixir, even if that means having a cable that goes directly from the screen to the Mango. That would allow me to use Scenic and I look forward to it.

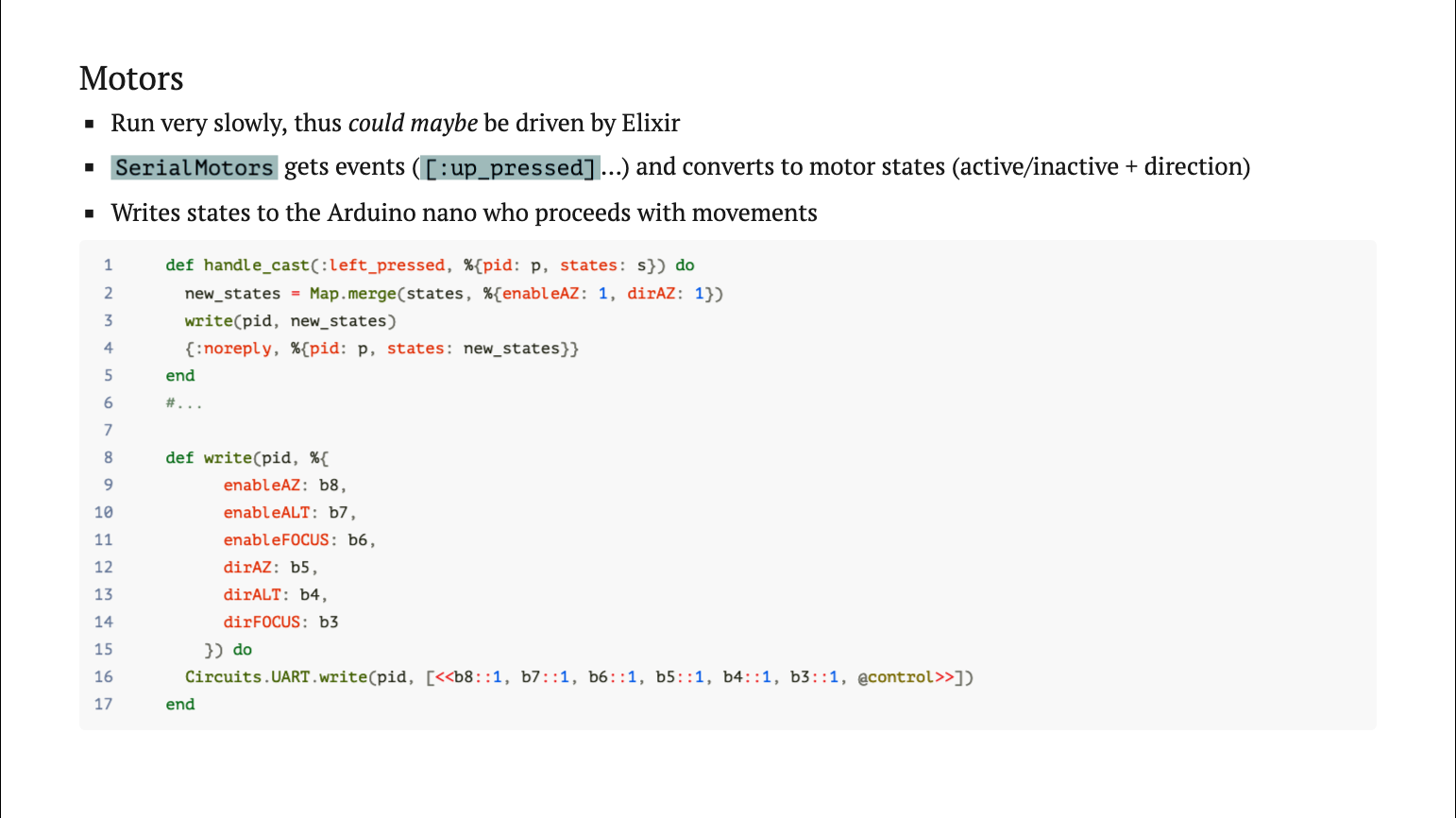

Motors. They follow a similar line of thinking, but in the other direction. The app converts individual events to motors state and direction. Since I have three motors, and each can go one way or the other, I pack that information into a single byte and the Arduino unpacks it to to control the motors. With more complex messaging you would add framing to the message, you would add headers to indicate the kind of message you send, but the general pattern is like that. Elixir makes it very easy to work with binary protocols. There’s a great blog post online that shows how to decode pngs with only function heads and pattern matching, and you can go quite far with that.

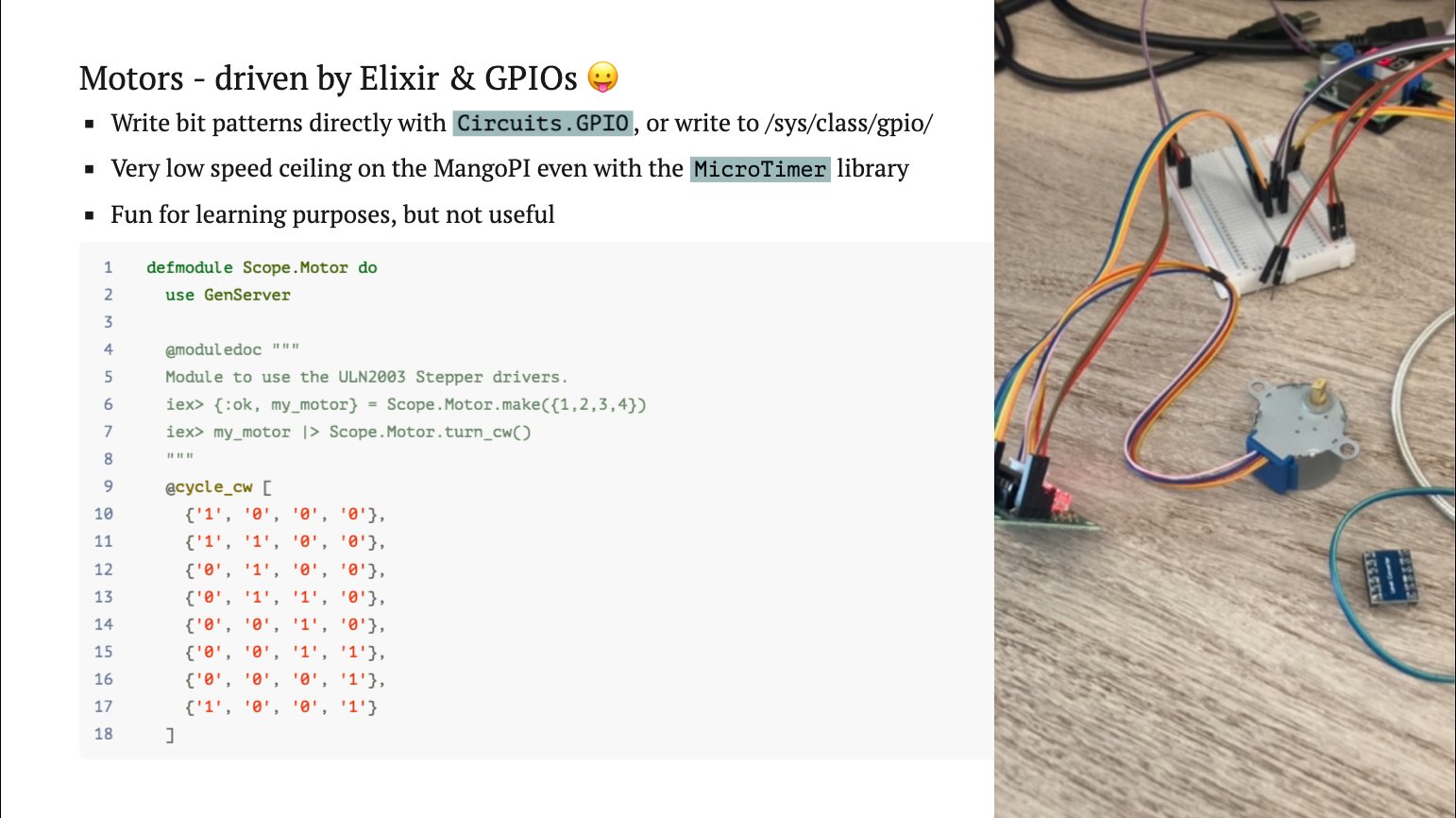

Note that you can also Drive motors from Elixir - it’s just not really efficient. To make a motor move, you have to control phase activations in a specific order to get the motor to make a step. But we don’t have much hard real time guarantees, and GPIO is quite slow, and your app has better things to do, so adding a microcontroller is generally the good way to handle motors. Still it’s interesting to learn how they work.

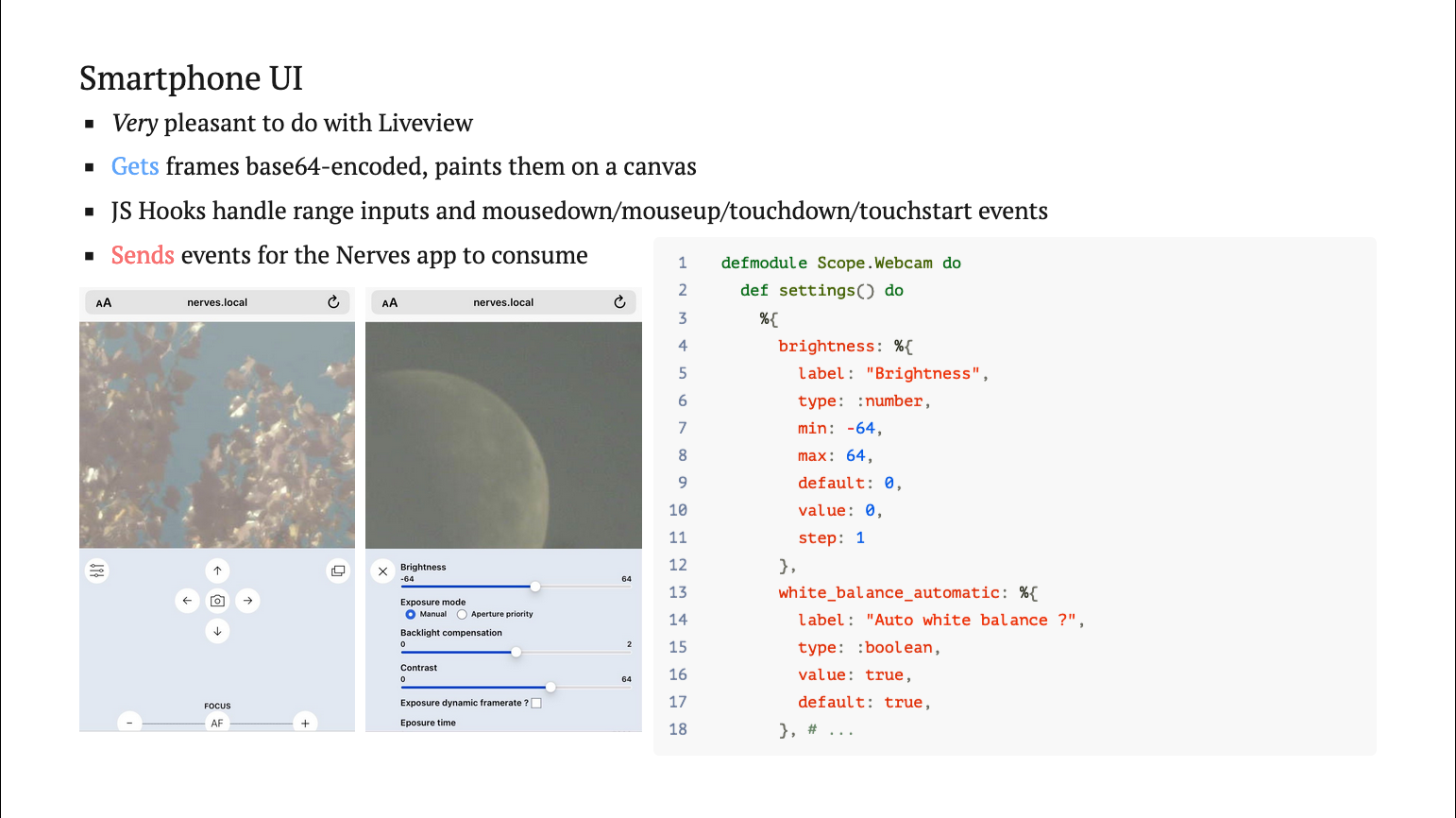

On the UI side, it’s just a small LiveView app, there’s nothing particular to that. Settings are declared in a plain Elixir module for now, which generates the UI, and in the future I’ll be able to parse them out of V4L2 output which is able to to list available settings and their ranges for any compatible camera. And that would allow me to change camera quite effectively.

We’re almost finished - just an image so you get the kind of things that a terrestrial telescope can see. Those are trees, they are pink, because the sensor is sensitive to infrared. You can see when refocusing, the obstruction of the the camera shows as a black circle in the light, and I kind of love the soft tones.

Next slide has a video that can be a bit flashing, so if that’s a problem tell me and I’ll just skip it.

Those are lives, now a few meters away, so I built this to be able to watch like birds at 50m, or even an insect at a few meters, which you cannot do with a regular telescope. I have a very long focusing range, it’s finally like an automated macro lens that can also observe at infinity, and the soft appearance comes from the mirror working at a non ideal distance, which I said at the beginning that would be relevant.

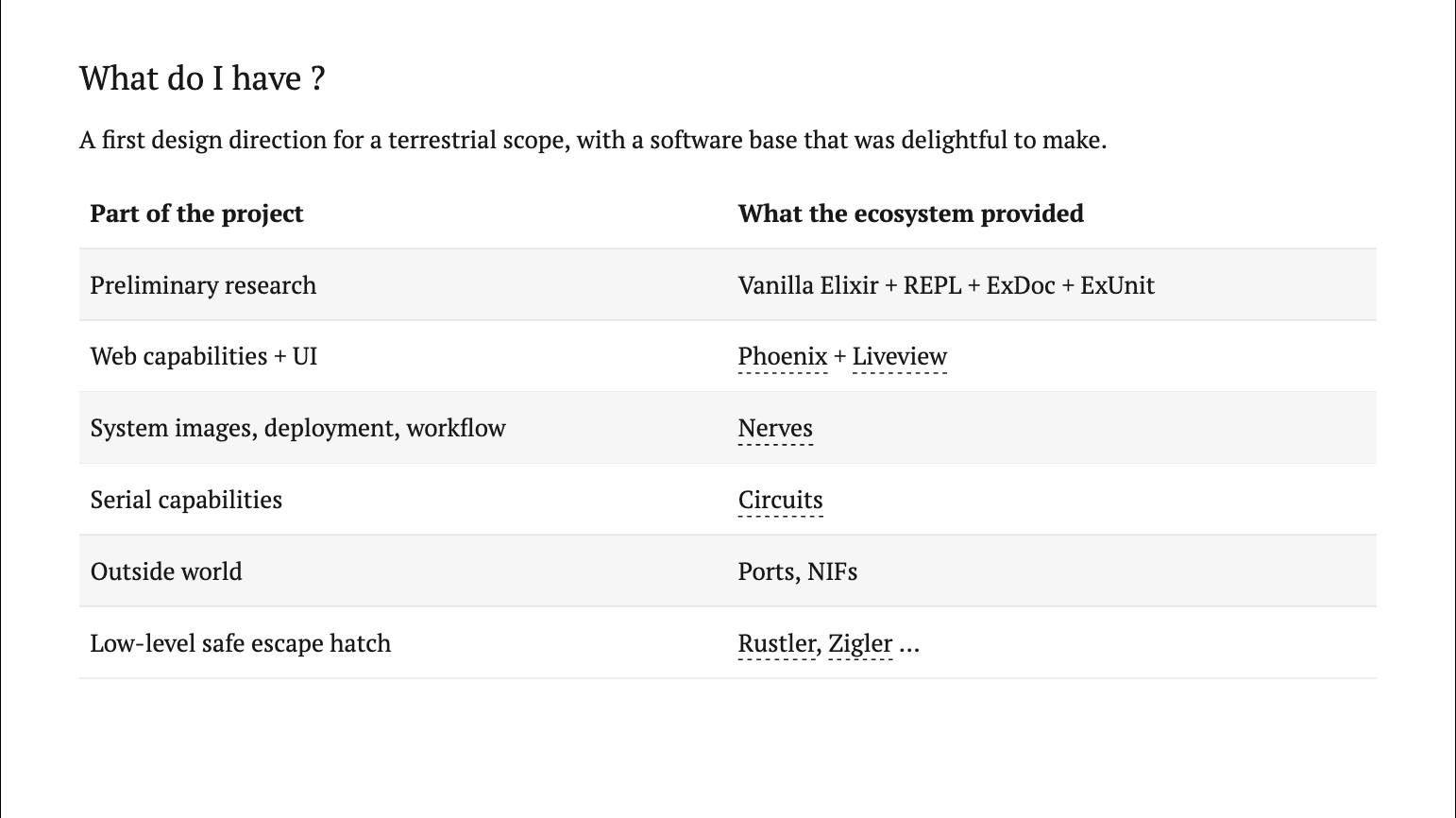

So, to wrap it up, what do I have ?

I have a wonky telescope prototype with working software that was a joy to make - everything I did, the ecosystem had a solution for, but you’re also free to drop to a lower level if you wish, that’s kind of neat.

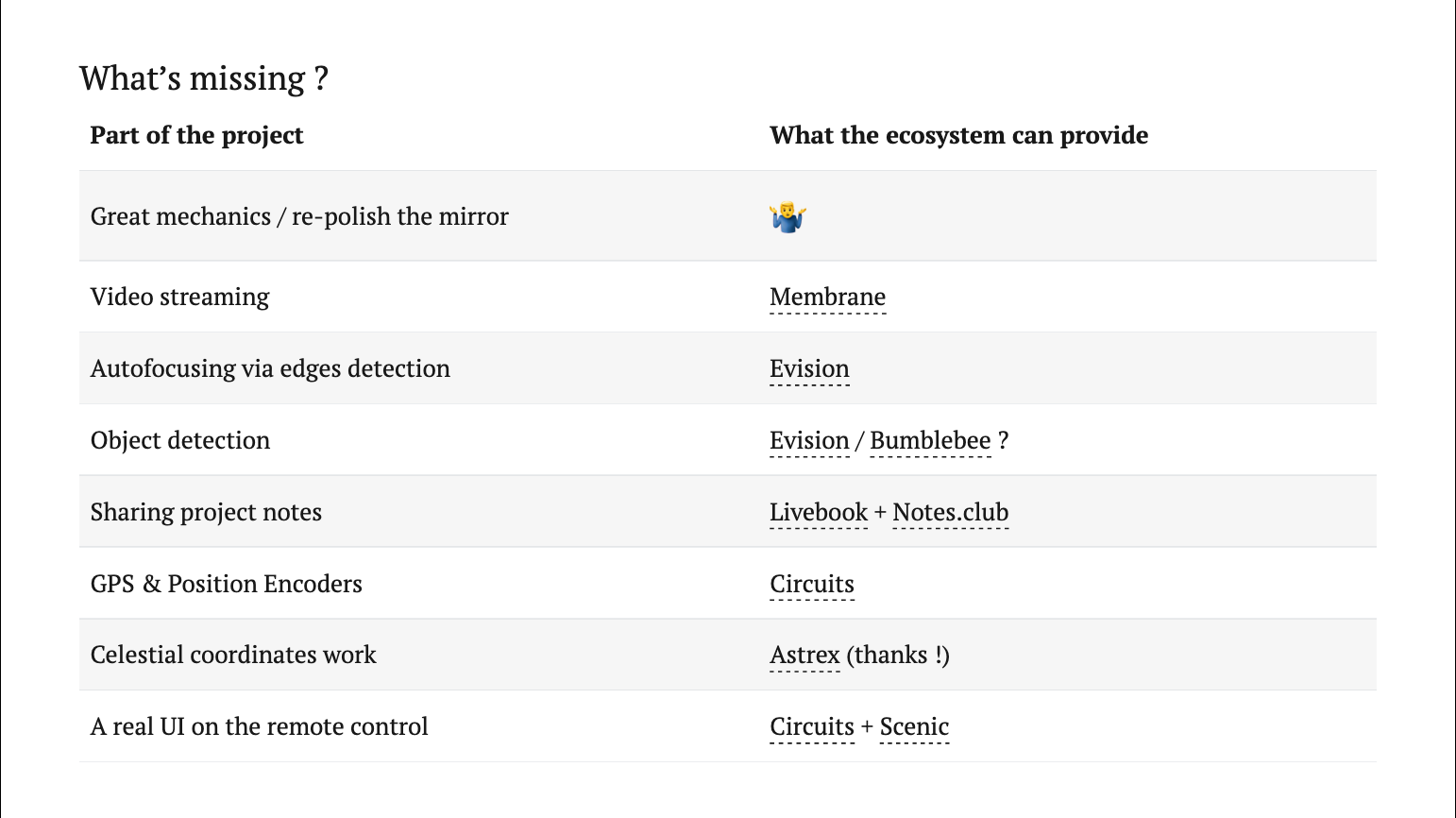

What’s missing ?

More interesting. A lot ! The project is maybe 10% done, as a scope is never done.

While researching the next steps I found that everything I had thought of, the ecosystem had an answer for that.

I thought I would have to implement celestial coordinates myself, but this July someone published a high quality library to hex for just that. So we maybe are two to drive telescopes with Elixir ? That’s neat.

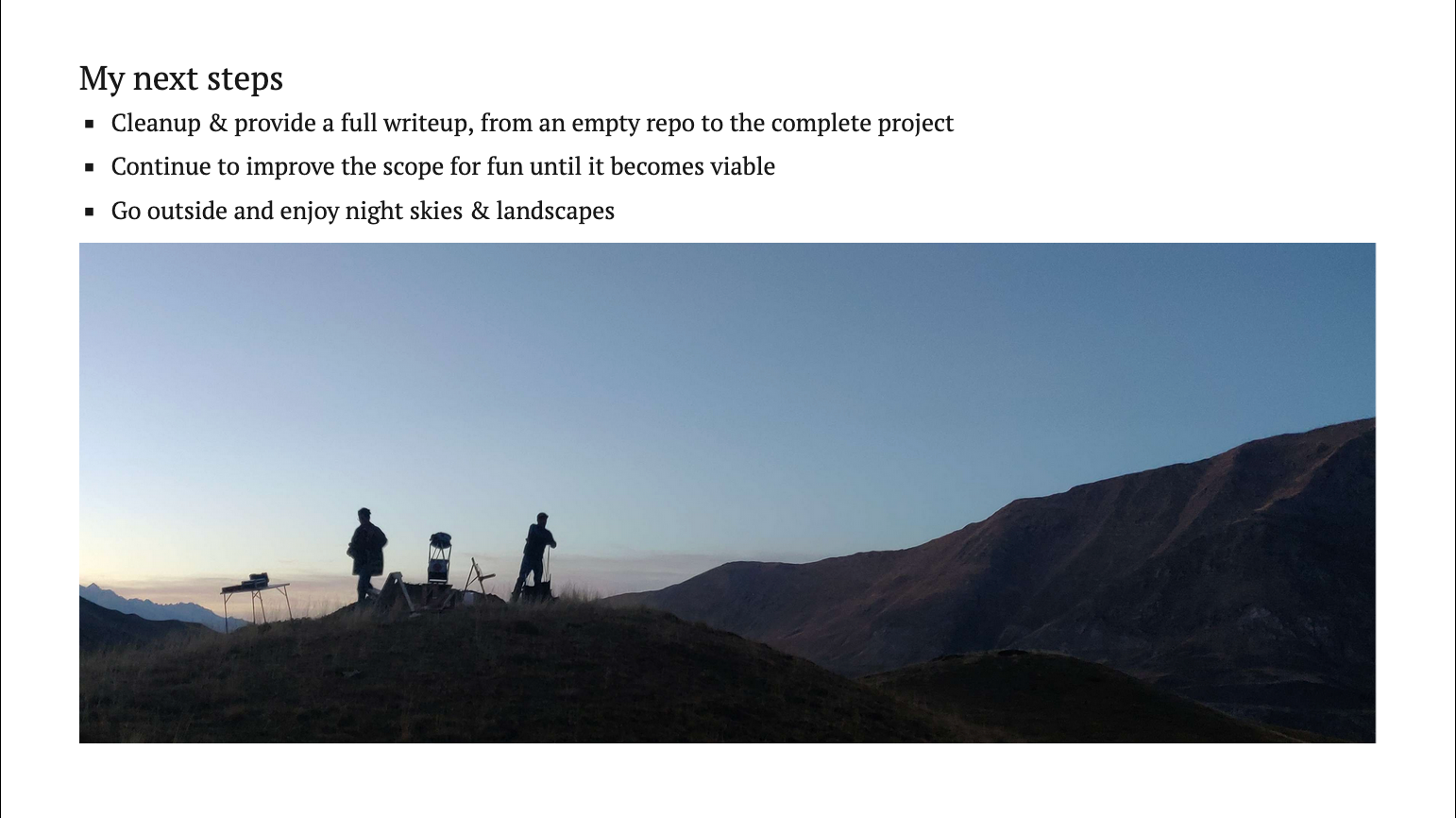

Next step, I will transform that into a full guide, from the empty repo to the complete project. I had blogged about that until the simulations part, but will now continue.

To conclude, I didn’t know nerves before that, and now I feel that everyone can have a very smooth first encounter with hardware in Elixir. If you come from the web, you are totally enabled to go outside of your usual work topic, and make something physical. So, thank you for your attention, and please hack away !

[Host (B.U.)]*

Okay, thank you very much that was very cool, I think we have time for a very quick question if anybody has one.

[Attendee, (Q.W.)]* Yes, thanks for sharing that this is such a cool project, and I had so much fun watching you go through that whole process. I guess I’m curious : what part of this project was the most surprising or most interesting to you ? There’s always little things that kind of surprise you.

[Me]

I guess, yeah I’ve been very pleasantly surprised by Nerves. For me embedded was like something very impressive.

I had built some physical things before but the usual process was get an Atmega, write some C++, when it comes to a nice UI… I don’t know !

So learning that Nerves, that I heard about for the first time (a bit late) but few years ago was that advanced and that comprehensive, I was like, wow. In general, it felt like I was not using libraries together and gluing them, but more like, if you want Vision, there’s Vision Elixir. If you want embedded, there’s embedded Elixir… and so on. We have very low fragmentation, you don’t have six or 10 medium quality things to do something, there’s more like sub ecosystems that have a very good shape today. That was kind of neat, I didn’t know any of these before.

* not sure if I could put your names there or not as it was a public event ? Just tell me if you stumble upon this post someday !